Pain is one of the most common reasons medical care is sought, and its prevalence in the United States is increasing dramatically.1 In many ways, while there are stronger and more extensive conventional tools, individuals appear to have a harder time controlling pain.

Recent NIH research demonstrates that the number of U.S. adults suffering from at least one painful health condition increased substantially from 120.2 million (32.9 percent) in 1997/1998 to 178 million (41 percent) in 2013/2014. This appears to have occurred even when the use of opioids, such as fentanyl, morphine, and oxycodone, for pain management more than doubled in the same period from 4.1 million (11.5 percent) in 2001/2002 to 10.5 million (24.3 percent) in 2013/2014.

While there are many contributors to this rise, one of the leading candidates is inflammation. More specifically, inflammation arises from various types of metabolic dysfunction and can contribute to the onset and progression of pain. Addressing inflammatory triggers in the context of chronic pain is key to finding approaches that may help reverse these trends.

Learn more about inflammation initiation and resolution.

Inflammation: Acute vs Chronic

There is often discussion of inflammation as the enemy. However, inflammation is required for life. Without inflammation, individuals would not be able to fight infection or recover from an injury. Inflammation is a critical component of healing. The body responds to threats by activating white bloods cells (i.e. macrophages, mast cells) and releasing a host of factors, including:

- Histamine

- Cytokines (e.g. interleukins, tumor necrosis factor)

- Prostaglandins

- Neurochemicals (e.g. serotonin, substance P)

- Hormones

These factors act immediately as well as by promoting downstream processes, such as gene expression to help defend and heal.2 When these essential frontline processes occur as planned, the most basic of human challenges are met and resolved.

Inflammation Resolution

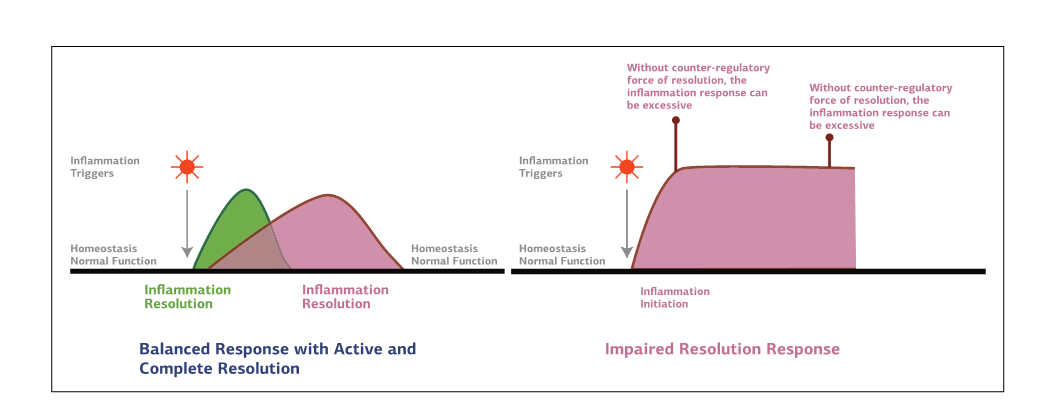

When inflammation occurs in a healthy individual, the process that returns tissues to a normal state is known as resolution. Unfortunately, when the process is prolonged, the ability to create resolution is limited and can proceed to what is termed low-grade or unresolved chronic inflammation. As noted in Figure 1, when chronic inflammation remains unresolved it can go on to cause tissue damage, which can lead to chronic diseases and/or pain.

Figure 1: Two Phases of Inflammation

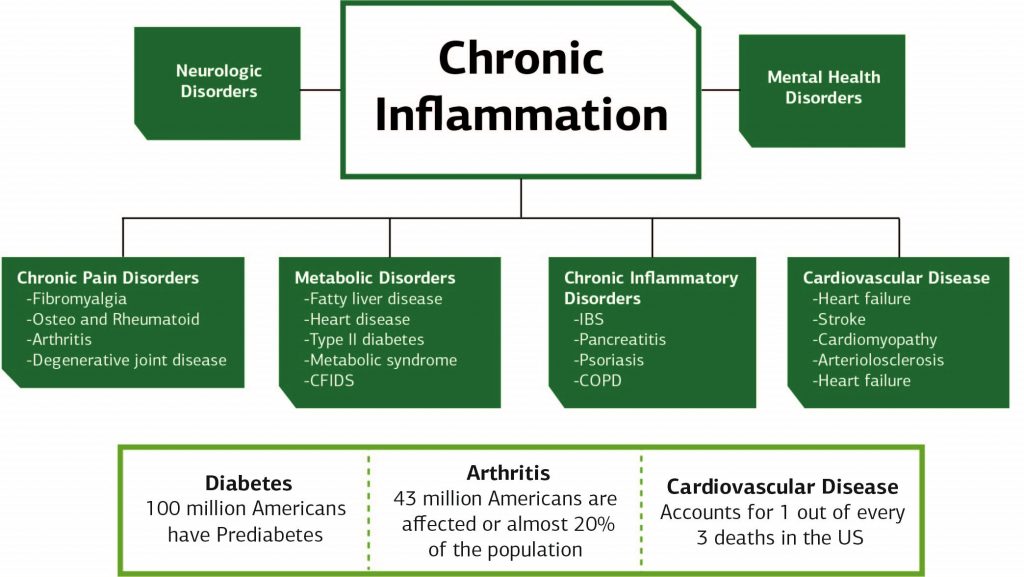

The scenario of unresolved chronic inflammation is especially prevalent with suboptimal diet, sedentary lifestyle, and obesity, where the inflammatory cascade is expanded into adipocytes and compounded by metabolic derangement, including insulin resistance. When this happens, it is crucial to help patients to reverse the metabolic underpinnings that contribute to inflammation. It is also important to provide approaches that aid in restoring the ability to resolve inflammation as a means of preventing and reducing pain.

Figure 2: Role of Lifestyle in Promoting Inflammation and Pain