Pain can be defined in many ways. In its most basic form, pain is, as defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain, “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage.”

While this definition provides a starting point for understanding an episode of pain, it is also important to realize that many other factors can also define pain:

- Chronicity or length of time pain is experienced (days vs. weeks vs. years)

- Category of injury (nociceptive, neuropathic, or central)

- Person experiencing pain (mood, medical state, metabolic status, and lifestyle)

- Context of pain (e.g. trauma)

In many ways, the factors surrounding pain can predict how the person affected will fare and they are important for planning better pain treatments.

Chronicity of Pain

Pain is often defined in terms of acute versus chronic. Acute pain is typically defined as less than several months in length. As pain persists beyond this time window, it is often termed as chronic. What is key is not only that the person has had the pain for a longer period of time but that the mechanisms that are promoting the pain are often different than those which initiated the pain. For example, a person with predominately left-sided neck pain from a whiplash injury who months later has contralateral pain that is spreading to other parts of their body is generating pain in completely different ways. While the treatments that might reduce acute pain are helpful initially, they may do little to reduce pain that becomes chronic and may be generated centrally as opposed to peripherally.

Category of Pain

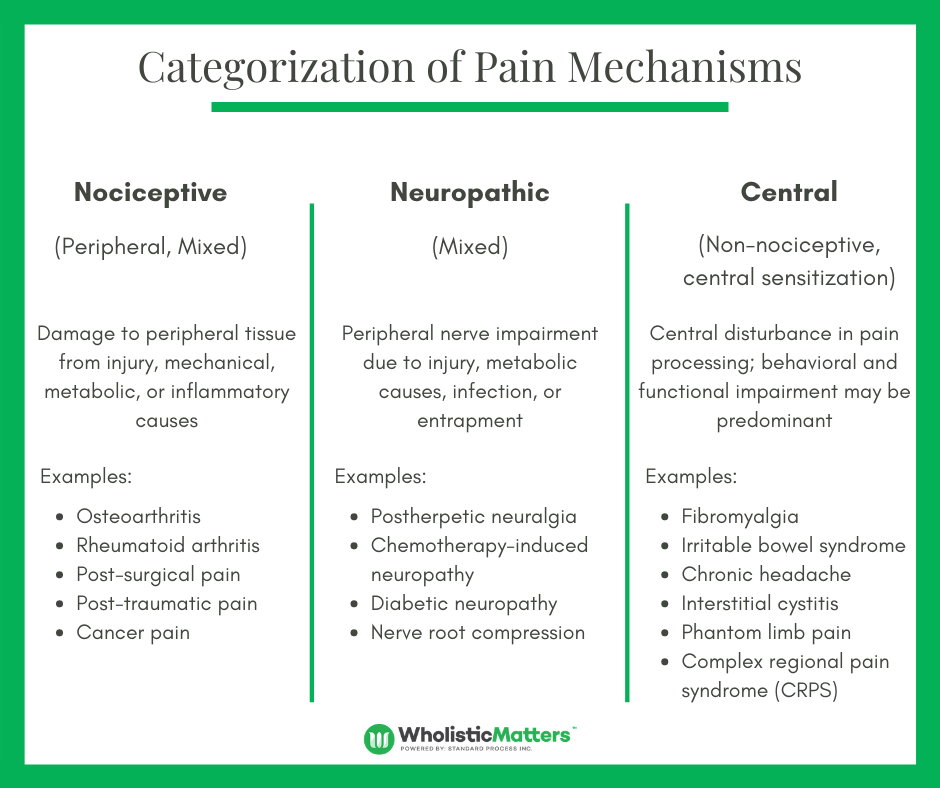

Pain can also be categorized based on the inciting or progressive events as noted in Figure 1. The category can be important at the onset of pain to know what treatments are best. For example, the acute whiplash injury would be treated differently than a person initially presenting for knee arthritis or post-chemotherapy neuropathy. Importantly, the category of pain can also evolve or involve multiple categories. This is the case in the example of chronic whiplash injury, which initiates as a nociceptive pain and evolves into a central phenomenon with spreading and spontaneous pain generation that requires additional and unique treatment.

Figure 1: Categorization of Pain Mechanisms (Adapted from Phillips K, Clauw DJ. Central pain mechanisms in chronic pain states – maybe it is all in their head. Best Prac Res Clin Rheumatol 2011;25(2): 141-54.)

How People Feel Pain

How people feel pain is initially and largely dependent on the category and context of pain. This occurs in a multi-step process that involves:

How people feel pain is initially and largely dependent on the category and context of pain. This occurs in a multi-step process that involves:

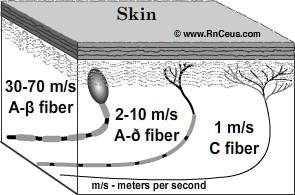

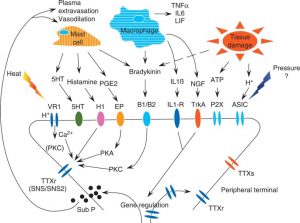

- Transduction of tissue injury: Pain receptors (nociceptors) are able to change (transduce) the injury (e.g. whiplash, hammer to the finger, hot stove, etc.) into an electrical signal that can more quickly communicate with the rest of the nervous system. Some types of injury (e.g. crush injuries, chemical injuries, etc.) cause a significant degree of chemical release (via prostaglandins), which can promote pain. The body has several types of nerve fibers including A fibers, which tend to travel more quickly, and C fibers, which travel slower and are more prone to cross communicating.

- Conversion of the Signal: An initial tissue injury converts to an electrical signal that travels from the site of injury to the spinal cord.

Spinal Cord Transmission: Transmission, also known as first, second, and third order transmission, involves signals coming from the periphery being recognized initially by the dorsal horn of the spinal cord.

Spinal Cord Transmission: Transmission, also known as first, second, and third order transmission, involves signals coming from the periphery being recognized initially by the dorsal horn of the spinal cord.- Brain Transmission: From the spinal cord, the signal is further transmitted to the brain: initially to the thalamus (the “switchboard”) and then to specific parts of the brain. The somatosensory cortex in the brain is responsible for sensing the pain (i.e. dull, sharp, burning, etc.). The frontal cortex is responsible for interpreting and thinking about the pain (i.e. I should walk with shoes on to avoid stepping on another tack). Finally, the limbic system is responsible for memory, fear, and emotional processing of the pain. The limbic system prompts an individual to remember the experience, to avoid repeating, and judge the experience (i.e. That was dumb! How could they leave those tacks out!)

The transmission of pain, in some ways, also sets up whether the pain will become chronic and/or amplified.

Person Experiencing Pain

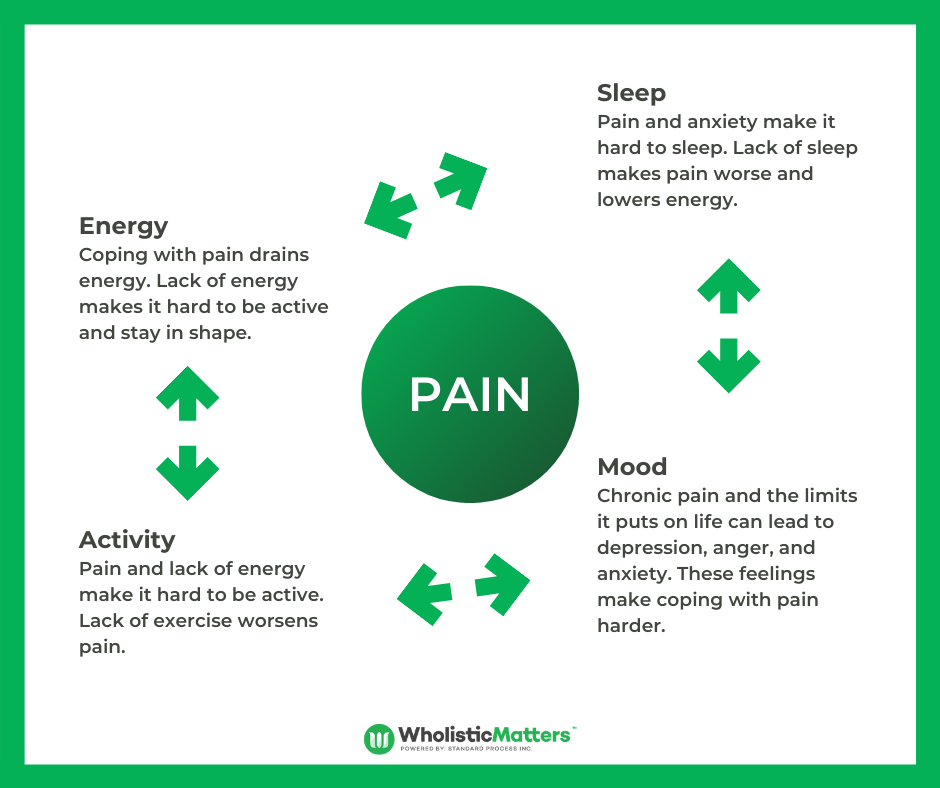

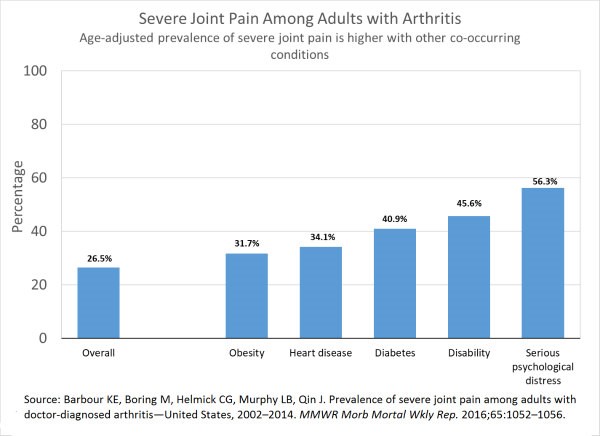

Many factors encompassing the person experiencing pain as well as how they feel and behave affect how pain is experienced and how it evolves. For example, individuals with an additional diagnosis of obesity and medical and psychological diagnoses have a higher prevalence and severity of arthritis as noted in Figure 3. In addition, lifestyle factors such as changes in sleep and physical activity can create a vicious cycle of pain as noted in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The Cycle of Chronic Pain (Adapted from https://www.fairview.org/patient-education/85785)

Figure 3: Severe Joint Pain Among Adults with Arthritis (https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/pain/text-version.htm)

Context of Pain: Trauma

In many cases, supporting someone in pain is about addressing an aspect of their life before the onset of pain. One of the most important concepts is the link between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and pain. ACEs can be determined through patient history by asking about previous trauma or through an ACE questionnaire. As research notes, the presence of ACEs significantly impacts the onset of pain, especially when there are pre-existing psychological syndromes. In this scenario it is important to be prepared to discuss ACEs and offer support, typically through behavioral interventions, such as trauma counselling, to support patients.

Trauma is also important to consider in the context of current pain episodes. Pain created in a traumatic setting (i.e. neck pain due to whiplash injury) can have a very different trajectory, both in the severity of pain as well as collateral issues, than a degenerative process (i.e. neck pain due to degenerative neck arthritis). In several studies, being able to provide interventions such as biofeedback or omega-3 supplementation can help to reduce the inflammation and holding pattern often created by acute traumatic injuries that will allow other long-term treatments to have improved efficacy.