Nutrients for Joint Support

Joints allow for movement where two or more bones meet, and healthy joints support healthy movement throughout the lifespan.1 While they vary in shape, size, and type, joints are an important part of the musculoskeletal system, and taking steps to ensure healthy joints can result in benefits for years to come. In this article, we’ll walk through some of the nutrient support for joints that have shown promise for supporting healthy maintenance and joint repair.

The Anatomy and Function of Joints

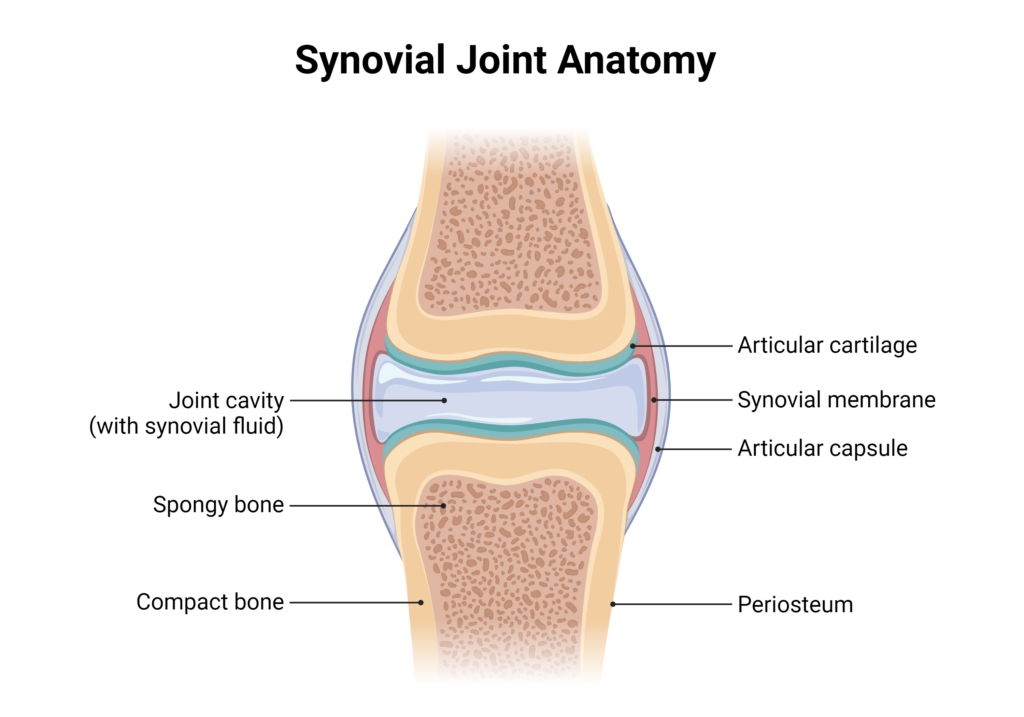

Joints consist of several components, each with a unique function in allowing or supporting movement.

Joint Structure

Cartilage covers the surface of a bone at a joint which helps reduce friction within the joint during movement.

Chondrocytes are the cells that are responsible for the production of collagen and the extracellular matrix that supports cartilaginous tissues in the joint. The synovial membrane lines and seals the joint capsule by secreting synovial fluid which helps lubricate the joint.

Image created using BioRender.com

Ligaments are tough, elastic bands of connective tissue that connect bones together and limit the joint’s movement. Tendons are also a type of tough connective tissue; however, they attach bone to muscles on each side that control the movement of the joint.

Finally, bursas are fluid-filled sacs between bones, ligaments, and nearby structures that help cushion the friction in a joint.

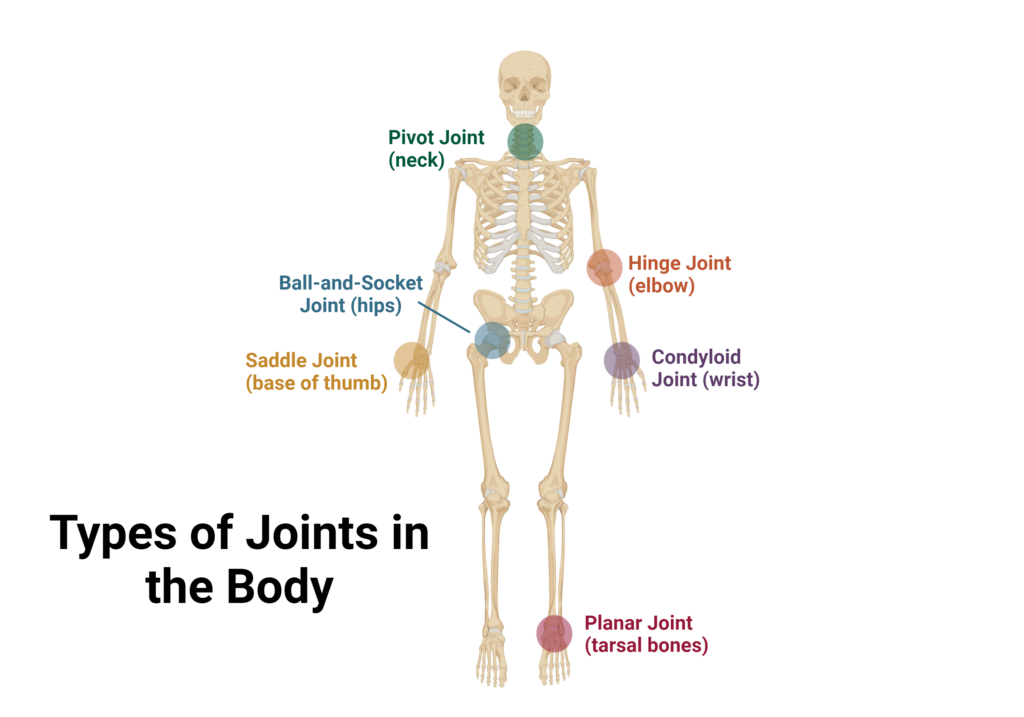

While most joints allow for movement, some do not move (fibrous joints) or allow for very little movement (cartilaginous joints). Synovial joints produce movement and can be broken down into six different types:1

- Ball-and-socket joints allow movement in all directions including backward, forward, sideways, and rotating movements.

- Saddle joints allow movement back and forth and from side to side but not rotating motion.

- Hinge joints allow bending and straightening.

- Pivot joints allow limited rotating movements.

- Planar joints allow for gliding movements.

- Condyloid joints allow for all types of movement except pivotal movements.

Image created with BioRender.com

How Joints Work

For joints that are moveable, contraction or relaxation of muscles that are attached to bones on either side of the joint control movement, with opposing actions often occurring. The precise movement will be determined by the type of joint as well as how many joints are involved in the movement.2

The synovial cavity and synovial fluid are also very important in the movement process. The synovial cavity contains blood vessels and nerves that communicate with the brain to relay the current position of the joint and signal pain if necessary.

Synovial fluid also helps the surfaces of the joint glide smoothly during movement and also absorbs shock by distributing pressure on the joint.2 When joints are kept still for a long period of time, the fibrous tissues that make up the outer layer of the joint capsule may shorten, which causes the joint capsule to shrink. When this occurs, the joint is no longer moveable.2

Common Joint Problems and Their Impact on Quality of Life

Because joints are complex nodes in the body, issues with any of the components can affect the entire joint. Acute joint problems can occur due to traumatic events such as dislocations, fractures, and sprains and strains. These commonly heal with rest quickly, but long-term consequences can arise.

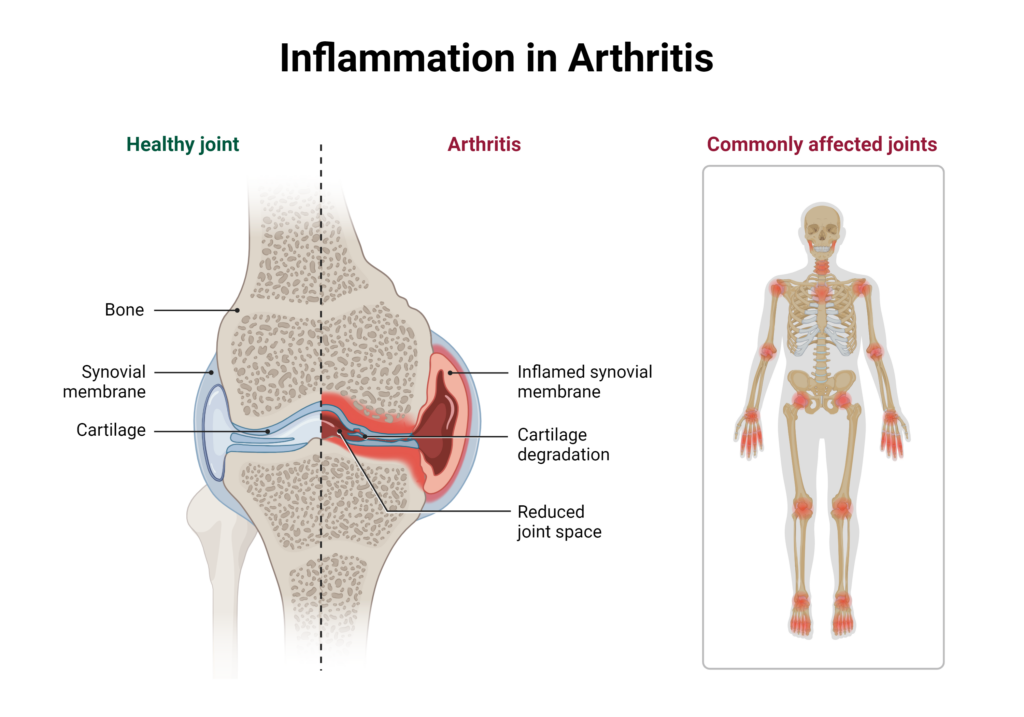

Chronic joint conditions tend to be related to inflammation. The most common joint condition is arthritis, characterized by inflammation in a joint that leads to irreversible bone and cartilage damage.

There are several types of arthritis, including rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and psoriatic arthritis. Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common type, and the prevalence of osteoarthritis is increasing at an alarming rate.3,4 Development and progression of OA involves many factors, including remodeling of subchondral bone, synovial inflammation, and loss of articular cartilage, some of which are driven by inflammatory cytokines.3,5

The inflammatory cytokines within joints stimulate the production of degrading enzymes, which causes further bone damage and cartilage degeneration, eventually leading to destruction of the joint.5

Oxidative stress in the joint can also activate cartilage signaling pathways and disturb chondrocyte homeostasis in OA.6 As OA progresses, it can result in chronic pain, loss of function, and reduced quality of life.5

Image created with BioRender.com

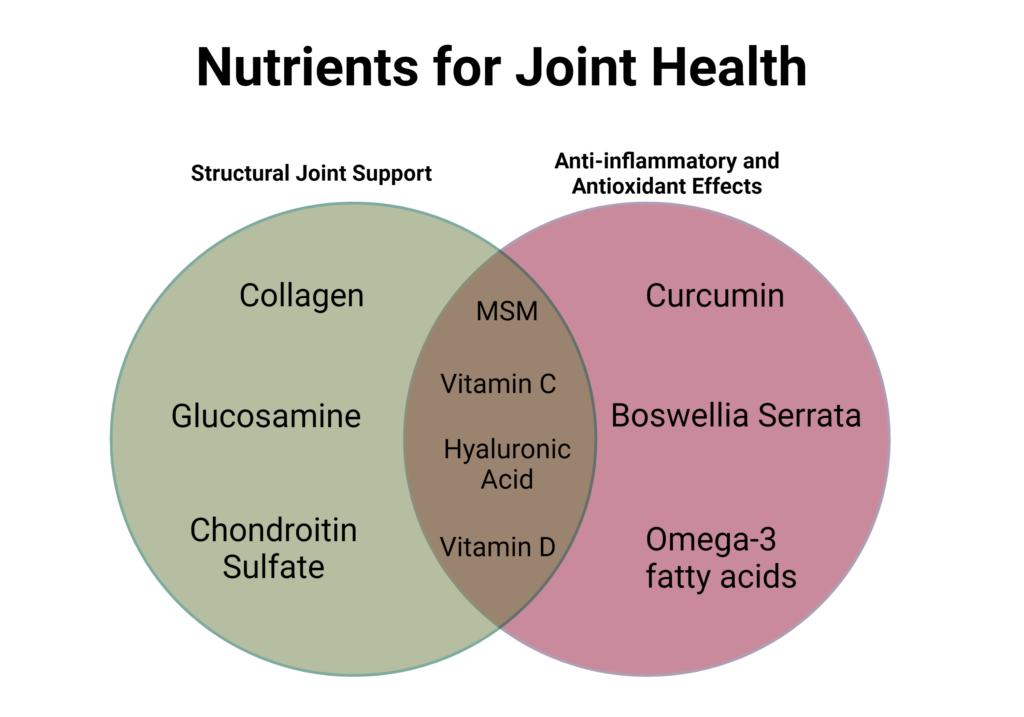

Nutrient Support for Joints

Collagen

Collagen is the most abundant protein in the extracellular matrix (ECM) in skeletal muscle tissue, providing structural support to skin, muscles, bones, and connective tissue.7 In the body, collagen production is supported by several micronutrients including vitamin C, copper, zinc and amino acids including proline and glycine. Because of its important role in maintaining joint structure, it is thought that supplementation with collagen may help promote the synthesis of connective tissue.7

Over 28 types of collagen exist, each with unique properties and benefits to the body. For example, undenatured native collagen and soluble native collagen possess a triple helix structure whereas gelatin and hydrolyzed collagen have undergone various degrees of processing through hydrolysis.7

The effect of collagen supplementation depends on several factors, including the structure, composition, and origin that contribute to its different properties.7 Native collagen is resistant to degradation upon digestion, maintaining its triple helix structure, and works via immune-modulatory mechanisms to inhibit inflammation.7

Native type II collagen is also the type of collagen that is most active in OA repair as the main protein in articular cartilage.7 Clinical studies have shown that native type II collagen helps relieve pain and improve joint function.7

Hydrolyzed collagen is more processed but resists intracellular hydrolysis which helps avoid degradation and allows for the delivery of bioactive peptides to joint tissues.7 Within the joint, these bioactive peptides protect chondrocytes and induce cartilage synthesis via chondrocyte stimulation in the ECM.7

While specific effects depend on the type of collagen, various types of hydrolyzed collagen have been shown to stimulate the synthesis of ECM compounds such as proteoglycans and type II collagen, induce chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation, increase the activity of osteoblasts, and decrease the activity of osteoclasts which all contribute to repairing cartilage in the joint.7

Many clinical trials use collagen from chickens, but it can also come from other animals, including pigs, cows, and fish.7 Native collagen is effective at a lower therapeutic dose compared to hydrolyzed collagen (40 mg/day compared to 5-10 g/day).7

Glucosamine and Chondroitin Sulfate

Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate are the most commonly used symptomatic slow-action drugs (SYSADOAs) for osteoarthritis, delivering a better safety profile and high tolerability than other pharmacological options.7 Glucosamine is a water-soluble amino monosaccharide that is involved in the synthesis of proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans which are core components of cartilage.8

Chondroitin is part of the ECM of articular cartilage, which is important in balancing osmotic pressure.8 As such, chondroitin may benefit cartilage resilience by providing the cartilage tissue with resistance and elasticity while glucosamine aids in cartilage maintenance.8

A meta-analysis of thirty clinical trials revealed that glucosamine was best suited for alleviating stiffness in the joint whereas chondroitin sulfate demonstrated a stronger ability to reduce pain symptoms as well as improve function.8

Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Omega-3 fatty acids are recommended for a variety of conditions including joint problems because of their strong anti-inflammatory effects.3 Within the joint, omega-3 fatty acids contribute to a healthy lipid profile in the matrix and chondrocytes of articular cartilage.3 Maintaining a healthy profile of lipids in the joint can help support joint health by opposing inflammation, cartilage degradation, and impaired chondrocyte structure.3

The Standard American Diet has a high ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids and this ratio is highly correlated to inflammation.3,4 In fact, overconsumption of omega-6 PUFAs has been associated with synovitis and cartilage damage in obese individuals.3,4 Studies have also found that high levels of omega-6 fatty acids accumulate in joints with OA, along with the corresponding pro-inflammatory eicosanoids and other lipid mediators of inflammation.3 Conversely, omega-3 fatty acids decrease the production of pro-inflammatory cytokine and eicosanoids, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) while also increasing the production of anti-inflammatory mediators called resolvins.3

Clinical studies investigating the ability of omega-3 fatty acids to improve joint health have had some mixed results but overall, they are promising. In one trial, there were greater benefits in the WOMAC pain scale (an assessment used to evaluate hip and knee osteoarthritis) and functional use scores from a lower dose (0.45 gram) compared to a high dose (4.5 g).9 In a separate study, supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids improved morning stiffness and pain.10

While clinical studies investigating supplementation can be challenging, results consistently indicate that a diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids and low in omega-6 fatty acids can reduce inflammation, relieve pain, and improve joint function.11 Omega-3 fatty acids can be found in fish oils as well as in flaxseed. Fish oils are a rich source of EPA and DHA while flaxseed contains alpha-linolenic acid which can be converted to EPA and DHA in the body.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is a key regulator of bone metabolism through vitamin D receptors.3 Interestingly, these receptors are expressed in OA patients within the articular cartilage, but not in healthy controls, indicating that vitamin D may be involved in joint health and damage directly or indirectly through endocrine effects.12,13 Vitamin D may also influence inflammation and cytokine synthesis.14

Several studies have linked low vitamin D status to poor joint health, including cartilage loss and OA progression and prevalence, although low vitamin D levels may be a general marker of ill health rather than a specific step in the development of joint problems.3,15,16

Clinical studies have found that vitamin D supplementation can improve muscle strength which indirectly supports joint health, decrease OA pain, increase symptomatic knee function, and improve structural and functional outcomes in individuals with OA in the knee.10, 17-20

Vitamin C

Vitamin C provides many benefits to the body, including supporting the immune system, functioning as an antioxidant, and serving as an important component in collagen synthesis.21 Specifically, vitamin C is a cofactor for enzymes that help stabilize the structure of collagen and promote collagen gene expression.22 Vitamin C also supports the healing of bones, tendons, and ligaments.23 As a powerful antioxidant, vitamin C helps maintain oxidative balance in joints which is critical for preventing oxidative stress that can contribute to joint problems.23

Individuals with OA were found to have significantly lower vitamin C intake compared to those without OA and in a large prospective study, supplementation with vitamin C over 10 years decreased the risk of developing OA by 11% compared to those who did not take any vitamin C supplement.24-26

The authors of this study concluded that vitamin C may help protect against OA but not delay the progression once it has developed.26 Other clinical evidence indicates that vitamin C supplementation may help reduce OA pain.3,4

Methylsulfonylmethane

Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) is naturally present in many foods and is a rich source of sulfur.6 Sulfur is the fourth most abundant mineral in the body and is present in large amounts in cartilage.6

MSM supports joint health by promoting osteoblast differentiation, regulating the expression of genes involved in bone formation, and promoting chondrogenesis, and exhibiting anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects.6,27 MSM can penetrate membranes and affect cells throughout the body, likely resulting in cellular crosstalk that helps dampen inflammation and oxidative stress.27 MSM may also help modulate the immune response.27

In clinical studies, MSM relieved joint pain and improved multiple measures of joint health including stiffness, swelling in joints, and impairment of physical function.28-31 In a study of healthy individuals without OA, MSM relieved mild knee pain, including wake-up pain, and standing pain, as well as improved general health and quality of life.6

The ability of MSM to help preserve cartilage has also been found to translate into improved range of motion and physical function.17 Taken together; these studies indicate that MSM may benefit many individuals with OA as well as those with mild joint pain before it has progressed to OA. MSM can be combined with other joint supporting agents including glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and Boswellia and type II collagen to support joint health.17

Emerging Nutrients and Novel Approaches

Hyaluronic Acid

Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a glycosaminoglycan consisting of D-glucuronic acid and N-acetylglucosamine units.32 HA is found in several tissues in the body, including in synovial fluid and the ECM of soft connective tissues.32 It is responsible for the viscosity of synovial fluid which functions as a lubricant for joint movements and helps with shock absorption.33

Hyaluronic acid also acts as a cellular signaling molecule, triggering the release of cytokines that stimulate chondrocytes to synthesize endogenous HA and proteoglycans to help prevent the degradation of cartilage as well as promote its regeneration.32 Finally, HA can reduce the production of pro-inflammatory mediators and reduce nerve sensitivity associated with OA pain.32

Scientific studies have demonstrated that joints afflicted by OA contain lower levels of HA compared to healthy joints and consequently, intra-articular injections of HA have been used to restore viscoelasticity in joints.32

Further studies have shown that injectable forms of HA are effective at relieving OA pain, on par or more effective than other therapeutic options such as NSAID medications and corticosteroid injections.32

Beyond pain relief, injectable HA may even help with the reconstitution of layers of the cartilage and improve chondrocyte density as well as reduce synovial inflammation.34 However, there is an increased burden on patients due to the cost, risk of infection, and repeated visits to a hospital to receive injections.33

Supplemental forms of HA have also been shown to be effective for joint health — improving WOMAC score, daily activity, pain and stiffness, and muscle function, among other measures.33

Curcumin

Curcumin is a polyphenol found in turmeric that exerts strong anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects.5 Several studies have found that curcumin can benefit individuals with OA, including improving physical performance texts and WOMAC pain index.35 In a study of rheumatoid arthritis patients, curcumin twice daily at 250 or 500 mg resulted in improvements in clinical systems and serum markers of inflammation.36

Several studies have demonstrated that curcumin at both a low and high dose (160 and 1500-2000 mg/day) can alleviate symptoms of OA in the knee and is similarly effective as NSAID agents, with better tolerability.37-39

While some studies have shown mixed results, overall curcumin supplementation appears to be safe, well-tolerated and improves inflammation and clinical symptoms of osteoarthritis.10

Boswellia Serrata

Boswellia serrata, also called Indian Frankincense, has been used for centuries as part of traditional Ayurvedic medicine to treat chronic inflammatory diseases, including osteoarthritis.40 In addition to its anti-inflammatory properties, it also possesses anti-arthritic and analgesic activity.40

Clinical trials have demonstrated that Boswellia serrata extract can help manage OA by reducing inflammatory mediators and oxidative stress.40 Boswellia serrata extract also improved physical function, reduced pain and stiffness, improve knee joint structure, and reduced spur formation.40

It has also been combined with other compounds for joint health to help promote joint health, including curcumin and ginger.40

Image created with BioRender.com

Incorporating Nutrients into Your Diet

For individuals seeking to incorporate joint-supporting nutrients into their meals, a healthy dietary pattern, such as the Mediterranean Diet (MedDiet), is a great option to obtain many beneficial compounds. The MedDiet is rich in seafood which provides omega-3 fatty acids, as well as fruits and vegetables that contain essential vitamins like vitamin C. Additionally, incorporating medicinal herbs into food preparation can help increase the intake of herbs such as turmeric.

For bioactive compounds like MSM, glucosamine and chondroitin, supplementation remains the best option. Consuming these supplements with food may promote consistent intake for best results and maximal joint benefits.

WholisticMatters is powered by Standard Process, a nutritional supplement company that’s family-owned and has operated for over 90 years. Standard Process offers many nutritional and whole food-based solutions.

- Juneja, P., Munjal, A., Hubbard, J.B. Anatomy, Joints. [Updated 2024 Apr 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507893/.

- org [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006-. In brief: How do joints work? [Updated 2021 Nov 11]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279363/.

- Thomas, S., Browne, H., Mobasheri, A., Rayman, M.P. (2018). What is the evidence for a role for diet and nutrition in osteoarthritis? Rheumatology, 57:iv61.

- Sophocleous, A. (2023). The Role of Nutrition in Osteoarthritis Development. Nutrients, 15:4336.

- Bañuls-Mirete, M., Ogdie, A., Guma, M. (2021). Micronutrients: Essential Treatment for Inflammatory Arthritis? Curr Rheumatol Rep, 22(12):87.

- Toguchi, A., Noguchi, N., Kanno, T., Yamada, A. (2023). Methylsulfonylmethane Improves Knee Quality of Life in participants with Mild Knee Pain: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients, 15:2995.

- Martinez-Puig, D., Costa-Larrion, E., Rubio-Rodriguez, N., Galvez-Martin, P. (2023). Collagen Supplementation for Joint Health: The Link between Composition and Scientific Knowledge. Nutrients, 15:1332.

- Zhu, X., Sang, L., Wu, D., Rong, J., Jiang, L. (2018). Effectiveness and safety of glucosamine and chondroitin for the treatment of osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Orthop Surg Res, 13:170.

- Hill, C.L., March, L.M., Aitken, D., et al. (2016). Fish oil in knee osteoarthritis: a randomised clinical trial of low dose versus high dose. Ann Rheum Dis, 75:23.

- Mathieu, S., Soubrier, M., Peirs, C., Monfoulet, L.-E., Boirie, Y., Tournadre, A. (2022). A Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Nutritional Supplementation on Osteoarthritis Symptoms. Nutrients, 14:1607.

- Deng, W., Yi, Z., Yin, E., Lu, R., You, H., Yuan, X. (2023). Effect of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation for patients with osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res, 18(1):381.

- Tetlow, L.C., Woolley, D.E. (2001). Expression of vitamin D receptors and matrix metalloproteinases in osteoarthritic cartilage and human articular chondrocytes in vitro. Osteoarthr Cartil, 9:423.

- Park, C.Y. (2019). Vitamin D in the prevention and treatment of osteoarthritis: From clinical interventions to cellular evidence. Nutrients, 11:243.

- Shen, M., Luo, Y., Niu, Y., et al. (2013). 1,25(OH)2D deficiency induces temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis via secretion of senescence-associated inflammatory cytokines. Bone, 55:400.

- Cao, Y., Winzenberg, T., Nguo, K., et al.(2013). Association between serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology, 52:1323.

- Bergink, A.P., Zillikens, M.C., Van Leeuwen, J.P., et al. (2016). 25- Hydroxyvitamin D and osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis including new data. Semin Arthritis Rheum, 45:539.

- Beaudart, C., Buckinx, F., Rabenda ,V., et al. (2014). The effects of vitamin D on skeletal muscle strength, muscle mass, and muscle power: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 99:4336.

- Tomlinson, P.B., Joseph, C., Angioi, M. (2015). Effects of vitamin D supplementation on upper and lower body muscle strength levels in healthy individuals. A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport, 2015;18:575.

- Sanghi, D., Mishra, A., Sharma, A.C., et al. (2013). Does vitamin D improve osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 471:3556.

- Zheng, S., Jin, X., Cicuttini, F., et al. (2017). Maintaining vitamin D sufficiency is associated with improved structural and symptomatic outcomes in knee osteoarthritis. Am J Med, 130:1211.

- Li, Y., Schellhorn, H.P. (2007). New developments and novel therapeutic perspectives for vitamin C. J Nutr, 137:2171.

- Pullar, J.M., Carr, A.C., Vissers, M.C.M. (2017). The Roles of Vitamin C in Skin Health. Nutrients, 9(8):866.

- DePhillipo, N.N., Aman, Z.S., Kennedy, M.I., Begley, J.P., Moatshe, G., LaPrade, R.F. (2018). Efficacy of Vitamin C Supplementation on Collagen Synthesis and Oxidative Stress After Musculoskeletal Injuries: A Systematic Review. Orthop J Sports Med, 6(10):2325967118804544.

- Jeong, Y., Lee, S.-W., Kim, Y., Kim, K., Seo, U., Bae, K.-H. (2019). Relationship of sociodemographic and anthropometric characteristics, and nutrient and food intakes with osteoarthritis prevalence in elderly subjects with controlled dyslipidemia: a cross-sectional study. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr, 28(4):837.

- Wang, Y., Hodge, A.M., Wluka, A.E., English, D.R., Giles, G.G., O’Sullivan, R., et al. (2007). Effect of antioxidants on knee cartilage and bone in healthy, middle-aged subjects: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Res Ther, 9(4):R66.

- Peregoy, J., Wilder, F.V. (2011). The effects of vitamin C supplementation on incident and progressive knee osteoarthritis: a longitudinal study. Public Health Nutr, 14(4):709.

- Butawan, M., Benjamin, R.L., Bloomer, R.J. (2017). Methylsulfonylmethane: Applications and Safety of a Novel Dietary Supplement. Nutrients, 9:290.

- Debbi, E.M., Agar, G., Fichman, G., Bar Ziv, Y., Kardosh, R., Halperin, N., et al. (2011). Efficacy of methylsulfonylmethane supplementation on osteoarthritis of the knee: A randomized controlled study. BMC Complement Altern Med, 11:50.

- Kim, L.S., Axelrod, L.J., Howard, P., Buratovich, N., Waters, R.F. (2006). Efficacy of methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) in osteoarthritis pain of the knee: A pilot clinical trial. Osteoarthr Cartil, 14:286.

- Pagonis, T.A., Givissis, P.A., Kritis, A.C., Christodoulou, A.C. (2014). Effect of methylsulfonylmethane on osteoarthritic large joints and mobility. Int J Orthop, 1:19.

- Usha, P.R., Naidu, M.U.R. (2004). Randomised, Double-Blind, Parallel, Placebo-Controlled Study of Oral Glucosamine, Methylsulfonylmethane and their Combination in Osteoarthritis. Clin Drug Investig, 24(6):353.

- Migliore, A., Procopio, S. (2015). Effectiveness and utility of hyaluronic acid in osteoarthritis. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab, 12(1):31.

- Oe, M., Tashiro, T., Yoshida, H., Nishiyama, H., Masuda, Y., Maruyama, K., et al. (2016). Oral hyaluronan relieves knee pain: a review. Nutr J, 15:11.

- Frizziero, L., Govoni, E., Bacchini P. (1998). Intra-articular hyaluronic acid in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: clinical and morphological study. Clin Exp Rheumatol, 16:441.

- Haroyan, A., Mukuchyan, V., Mkrtchyan, N., Minasyan, N., Gasparyan, S., Sargsyan, A., et al. (2018). Efficacy and safety of curcumin and its combination with boswellic acid in osteoarthritis: a comparative, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. BMC Complement Altern Med, 18:1.

- Amalraj, A., Varma, K., Jacob, J., Divya, C., Kunnumakkara, A.B., Stohs, S.J., et al. (2017). A novel highly bioavailable curcumin formulation improves symptoms and diagnostic indicators in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, two-dose, three-arm, and parallel-group study. J Med Food, 20:1022.

- Kuptniratsaikul, V., Dajpratham, P., Taechaarpornkul, W., et al. (2014). Efficacy and safety of Curcuma domestica extracts compared with ibuprofen in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a multi-center study. Clin Interv Aging, 9:451.

- Gupte, P.A., Giramkar, S.A., Harke, S.M., et al. (2019). Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of capsule longvida® optimized curcumin (solid lipid curcumin particles) in knee osteoarthritis: A pilot clinical study. J Inflamm Res, 12:145.

- Shep, D., Khanwelkar, C., Gade, P., Karad, S. (2019). Safety and efficacy of curcumin versus diclofenac in knee osteoarthritis: A randomized open-label parallel-arm study. Trials, 20:214.

- Majeed, M., Majeed, S., Narayanan, N.K., Nagabhushanam, K. (2019). A pilot, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to assess the safety and efficacy of a novel Boswellia serrata extract in the management of osteoarthritis of the knee. Phtyother Res, 33:1457.