Natural Biofilm Disruptors for Human Health

The power of biofilm disruption lies in its potential to dismantle intricate microbial communities, offering a key intervention against bacterial infections that involve biofilm formation. Natural biofilm disruptors such as phytochemicals, herbs and foods like garlic and kale, showcase promising capabilities in reducing biofilm growth and addressing related health challenges.

What are Biofilms?

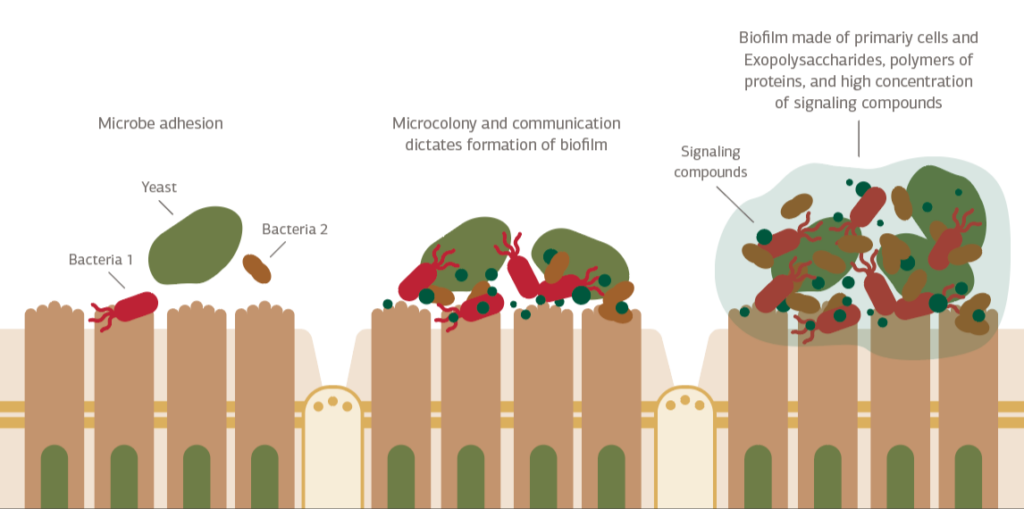

Biofilms are complex formations of microbial cells, such as bacteria, fungi, archaea, and protozoa, contained in extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) that convey benefits to the enclosed community.1 Within this EPS matrix, the metabolism of the bacteria and fungi changes. Through bacterial-fungal interactions (BFI), the biofilm behaves differently than the individual microbial species would if they were independent. Together, these changes and interactions result in protection for the biofilm. The biofilm matrix also controls the release of gases, nutrients, and antimicrobial substances.1

Biofilms consist of single or multiple bacterial strains along with other microorganisms, such as the yeast C. albicans.1 Yeasts are especially important in biofilm development, coordinating with bacteria and tipping a healthy microbial balance towards a more pathogenic composition. Mixed species biofilms are particularly concerning as they typically display greater mass, increased cell count, enhanced metabolic activity, increased tolerance to antimicrobial agents, and changes in their organization and structure that make them more difficult to combat.1

Where do Biofilms Form?

Biofilms can occur on a variety of surfaces, including external and internal surfaces. They are common in the environment as well as on medical equipment and devices and commercial equipment.2 While these biofilms have important implications for human health, the more direct consequences emerge from biofilms that occur within the body.

Found on mucosal surfaces in locations such as the ears, lungs, and gastrointestinal (GI) tract, biofilms that reside in the body can form, grow, mature, and spread to other locations with serious consequences.

How Does Biofilm Formation Happen?

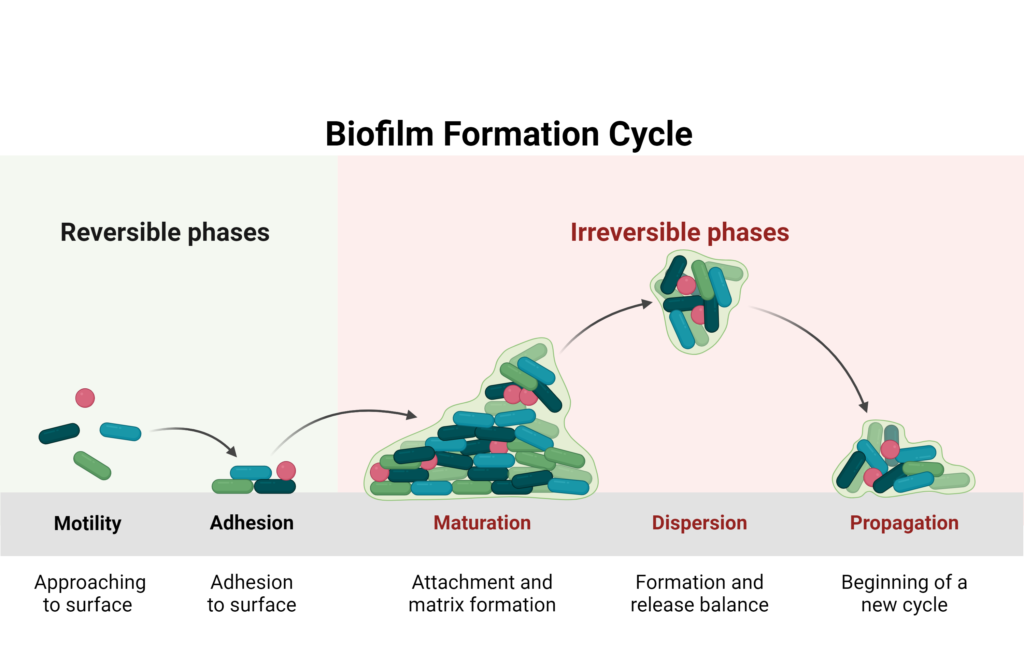

Biofilm formation is a three-step process. First, microbial cells adhere to a surface and begin secreting extracellular polymeric substances to form the biofilm matrix.1 Next, the biofilm matures as microbial colonies form and the biofilm helps excrete wastes and disperse nutrients.1 Finally, microbial cells from the mature biofilm escape and disperse to form a new biofilm in a different location.1

The formation of biofilms is affected by multiple factors including temperature, pH, nutrient content in the surrounding microenvironment, properties of the surface to which it adheres, and quorum sensing- an intercellular signaling mechanism that helps the biofilm communicate via chemical signals.1

Created with BioRender.com

Biofilms provide a stable, protective environment for the microbial cells that are contained within the matrix.1 It prevents the penetration of antibiotics and also protects bacteria and other microbial cells from changes in blood pH, osmotic pressure, and nutrient deficiency.1,3 It also evades the immune system by inhibiting immune cell function, changing gene expression, offering mechanical protection, and inhibiting recognition by the immune response.1,3

How Biofilms Affect Human Health

These protective effects can make it challenging for the body to naturally break down a biofilm, which can result in chronic symptoms and issues arising from the presence of a biofilm.

It is estimated that more than 80% of bacterial infections involve biofilm formation.1 This includes conditions like urinary tract infections, cystic fibrosis, and periodontitis.1 Cells in a biofilm can also disperse to other locations in the body where the presence of bacteria or fungi can cause health issues. A deeper understanding of the role of bacterial biofilms, including specific species involved, can help inform a better strategy for inhibiting the growth and development of biofilms.

Biofilm’s Role in the Pathogenesis of Disease

Multispecies biofilms can occur throughout the body, contributing to severe inflammatory and autoimmune conditions as well as chronic infections, although particular attention has been paid to the auditory, cardiovascular, and digestive systems.1

Within the auditory system, biofilm formation can result in conditions such as otitis media.1 These middle ear infections are especially prevalent in children under three years of age and can result in hearing loss.1

Biofilms can also grow within the cardiovascular system, for example on heart valves, or travel to the cardiovascular system from a distant location.4 Biofilms in the cardiovascular system may also be the reason behind stress-induced heart attacks. Stress hormones trigger biofilm breakdown in fatty plaques in arteries, releasing bacteria as well as the plaques that can then cause heart attacks or strokes.5

When biofilms grow in the GI tract, they can pose significant challenges to patients in terms of symptoms and treatments. The digestive tract provides the perfect environment for biofilm formation due to the abundance of nutrients that it can use to thrive. Biofilms in the GI tract have been linked to several conditions, including Crohn’s disease, irritable bowel syndrome, and ulcerative colitis.6,7 Research investigating the role of biofilms in various GI conditions can help inform the development of more effective therapeutic strategies, especially for GI conditions that are difficult to manage.

Natural Biofilm Disruptors

Breaking down a biofilm can be challenging. Antibiotic treatments commonly used for bacterial infections may reduce biofilm but cannot eliminate it, and often come with significant side effects.3 However, several herbs and foods have been found to act as biofilm disruptors.

Phytochemicals

Several phytochemicals and bioactive compounds have demonstrated the ability to disturb microbial biofilm development. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), ellagic acid, berberine, quercetin, and linoleic acid have all demonstrated anti-biofilm actions against various bacterial strains, including E. coli and S. aureus.3 Curcumin has also demonstrated strong activity against biofilms.3

While each phytochemical displays unique mechanisms of action against biofilms, some common pathways include interrupting quorum sensing pathways (quercetin), cleaving peptidoglycan in the matrix (EGCG), and influencing gene expression that affects biofilm formation and metabolism (curcumin).3

Foods, Herbs, and Supplementation

Several foods and herbs can support gut health by disrupting biofilm metabolism. Garlic has been used for many years as a natural remedy for a variety of gut issues as well as for its anti-microbial and anti-fungal effects.8,9 Garlic can also positively influence the composition of the gut microbiome, correcting dysbiosis and alleviating inflammation.10,11

Maintaining a healthy gut environment is critical in preventing further formation of biofilm as biofilms can release pathogenic bacteria that can then invade other areas.12 Therefore, garlic may naturally support gut health through three mechanisms: anti-microbial effects, anti-biofilm actions, and supporting the growth of beneficial bacteria in the gut microbiome.

The cruciferous vegetable kale also supports a healthy gut environment and can inhibit biofilm formation. Like garlic, kale demonstrates strong antimicrobial and anti-biofilm activities. The presence of isothiocyanates in kale can damage cell membranes, deplete ATP, and decrease pH, all of which make it difficult for a biofilm to survive and grow.13 Kale also helps increase the diversity of the gut microbiome, pushing it away from a state of dysbiosis and towards microbiome balance.14

As evidenced, natural biofilm disruptors from the whole food matrix or via supplementation can significantly enhance gut health and help break down biofilms.

Did you know Wholistic Matters is powered by Standard Process? Learn more about healthcare practitioner benefits.

- Zhao, A., Sun, J., Liu, Y. (2023). Understanding bacterial biofilms: From definition to treatment strategies. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 13:1137947.

- Donlan, R.M. (2002). Biofilms: Microbial Life on Surfaces. Emerg Infect Dis, 8(9):881.

- Roy, R., Tiwari, M., Donelli, G., Tiwari, V. (2018). Strategies for combating bacterial biofilms: A focus on anti-biofilm agents and their mechanisms of action. Virulence, 9(1):522.

- Høiby, N., Ciofu, O., Johansen, H.K., et al. (2011). The clinical impact of bacterial biofilms. Int J Oral Sci, 3:55.

- Reardon, S. (2014). Bacteria implicated in stress related heart attacks. Nature, doi:10.1038/nature.2014.15396.

- Baumgartner, M., Lang, M., Holley, H., et al. (2021). Mucosal Biofilms Are an Endoscopic Feature of Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology, 161(4):1245.

- Hoarau, G., Mukherjee, P.K., Gower, C., et al. (2016). Bacteriome and Mycobiome Interactions Underscore Microbial Dysbiosis in Familial Crohn’s Disease. mBio, 7:e01250.

- Li, W.R., et al. (2016). Antifungal activity, kinetics and molecular mechanism of action of garlic oil against Candida albicans. Sci Rep, 6:22805.

- Bhatwalkar, S.B., Mondal, R., Krishna, S.B.N., Adam, J.K., Govender, P., Anupam, R. (2021). Antibacterial Properties of Organosulfur Compounds of Garlic (Allium sativum). Front Microbiol, 12:613077.

- Sunu, P., Sunarti, D., Mahfudz, L.D., Yunianto, V.D. (2019). Prebiotic activity of garlic (Allium sativum) extract on Lactobacillus acidophilus. Vet World, 12:2046.

- Chen, K., Xie, K., Liu, Z., Nakasone, Y., Sakao, K., Hossain, A., Hou, D.-X. (2019). Preventive Effects and Mechanisms of Garlic on Dyslipidemia and Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis. Nutrients, 11:1225.

- Buret, A.G., Allain, T. (2023). Gut microbiota biofilms: From regulatory mechanisms to therapeutic targets. J Exp Med, 220(3):e20221743.

- Hu, W.S., Nam, D.M., Choi, J.Y., Kim, J.S., Koo, O.K. (2019). Anti-attachment, anti-biofilm, and antioxidant properties of Brassicaceae extracts on Escherichia coli O157:H7. Food Sci Biotechnol, 28:1881.

- Shahinozzaman, M., Raychaudhuri, S., Fan, S., Obanda, D.N. (2021). Kale Attenuates Inflammation and Modulates Gut Microbial Composition and Function in C57BL/6J Mice with Diet-Induced Obesity. Microorganisms, 9(2):238.