Homocysteine, Cardiovascular Health, and the Role of Vitamin B6

Summary

Chronically elevated homocysteine can exert harmful effects on the heart and blood vessels, but ensuring adequate vitamin B6 intake can support both homocysteine metabolism and cardiovascular health.

What is Homocysteine?

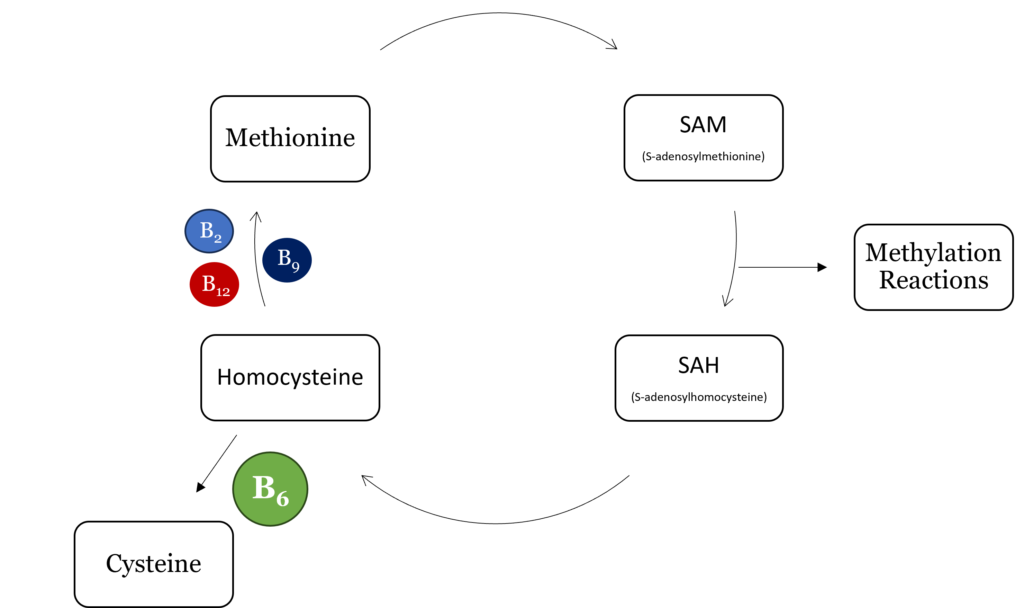

Homocysteine is a sulfur-containing, nonprotein amino acid that is formed from methionine and cysteine.1,2 It is involved in one-carbon metabolism and is critical for methylation reactions in the body. One-carbon metabolism requires four B vitamins, riboflavin (B2), pyridoxal (B6), folate (B9), and vitamin B12, as cofactors or coenzymes for various enzymes. Deficiency in one or more of these nutrients can result in abnormally high homocysteine levels.1 Numerous studies have shown that elevated homocysteine, a condition called hyperhomocysteinemia, negatively affects cardiovascular health.1,2

As part of one-carbon metabolism, homocysteine undergoes methylation to form methionine which then forms S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), the universal methyl donor for all methylation reactions in the body. Upon methylation of a target compound, SAM becomes S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) which is then hydrolyzed to homocysteine. From here, homocysteine can be re-methylated to form methionine, beginning the cycle again, or converted to cysteine via cystathionine β-synthase and cystathionase, both of which require vitamin B6 as a cofactor.

Low homocysteine, or hypohomocysteinemia, is associated with peripheral neuropathy and can negatively impact cellular processes.2 Homocysteine serves as a storage form of sulfur and a source of methyl groups, and as such, low levels can affect any reaction requiring sulfur as well as methylation reactions, including epigenetic modifications.2 Additionally, homocysteine is involved in the synthesis of glutathione which can cause decreased glutathione levels and increased susceptibility to oxidative stress during hypohomocysteinemia.2

Hyperhomocysteinemia, or elevated homocysteine, is associated with several disease states, including multiple cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and underlying risk factors.2 Elevated homocysteine levels have been positively associated with coronary artery disease presence and severity, arterial stiffness, risk of stroke in elderly individuals, and both diastolic and systolic blood pressure.1,3,4 Several underlying conditions can lead to hyperhomocysteinemia:1,2

- Genetic polymorphisms in genes involved in homocysteine metabolism

- B-vitamin deficiencies including vitamins B6, B9, and B12

- Enzyme deficiencies of cystathionine β-synthase, methionine synthase, or 5-methyltetrahydrofolate reductase

- Some chronic diseases including renal disease

- Select pharmaceutical drugs

- Demographic factors such as old age or menopause

Role of Vitamin B6 in Managing Homocysteine Levels

Numerous studies have demonstrated that blood levels of vitamin B6 are inversely related to total homocysteine.1 A more direct cause-and-effect relationship was established by depleting vitamin B6, which resulted in accumulation of homocysteine.1,5 When vitamin B6 status was restored, homocysteine decreased, indicating a direct ability of vitamin B6 to influence homocysteine levels.5

Mechanistically, vitamin B6 is a cofactor for the enzymes cystathionine β-synthase and cystathionase, which together convert homocysteine to cysteine.6 When vitamin B6 is low, these enzymes cannot do their job, resulting in a build-up of homocysteine and depletion of glutathione, a lose-lose situation that negatively affects cardiovascular health.

What Homocysteine Levels Mean for Cardiovascular Health

Since the 1990s, elevated homocysteine has been recognized in the literature as an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis.1 Because of its significant effects on heart health, scientists have spent decades trying to elucidate the mechanisms by which excess homocysteine negatively affects cardiovascular health.

First, it causes endothelial damage, directly injuring endothelial cells in pre-clinical models, which reduces vascular endothelial integrity and elevates blood pressure.1 Homocysteine may also affect endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells which results in changes to the structure and function of arteries, endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, degradation of the arterial wall, and inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), a critical regulator of endothelial function and homeostasis.1

Cholesterol and Inflammation

Homocysteine negatively affects other contributors to CVD, including cholesterol and inflammation. It reduces high-density lipoprotein (HDL), a protective lipoprotein that removes cholesterol from circulation while increasing the activity of HMG CoA Reductase, an enzyme involved in cholesterol synthesis.1,7

This results in increased cholesterol synthesis which promotes atherosclerosis and CVD.1 Elevated homocysteine can also influence the epigenetic regulation of genes involved in oxidative stress in endothelial cells.1 Finally, homocysteine may enhance the negative effects of other risk factors for CVD including hypertension, smoking, dyslipidemia, and inflammation.1

Clinical studies investigating the ability of B6 supplementation to decrease homocysteine have produced some positive results, but overall the results have been inconsistent. In healthy elderly individuals, supplementation with low-dose vitamin B6 reduced plasma total homocysteine by about seven percent.8 However, other B vitamins, alone or in combination, may be more effective at lowering homocysteine.8 While acute treatment with vitamin B6 may not immediately lower homocysteine and counteract its detrimental effects on cardiovascular health, a healthy diet that is abundant in B vitamins can support healthy homocysteine metabolism and overall health in the long-term.

WholisticMatters is powered by Standard Process, a nutritional supplement company family-owned and operated for over 90 years. Standard Process offers many nutritional solutions.

- Ganguly, P., Alam, S.F. (2015). Role of homocysteine in the development of cardiovascular disease. Nutr J, 14:6.

- Pizzorno, J. (2014). Homocysteine: Friend or Foe? Integr Med, 13:8.

- Shenov, V., Mehendale, V., Prabhu, K., Shetty, R., Rao, P. (2014). Correlation of serum homocysteine levels with the severity of coronary artery disease. Ind J Clin Biochem, 29(3):339.

- Zhang, S., Yong-Yi, B., Luo, L.M., Xiao, W.K., Wu, H.M., Ye, P. (2014). Association between serum homocysteine and arterial stiffness in elderly: a community-based study. J Geriatr Cardiol, 11:32.

- Shultz, T.D., Hansen, C.M. (1998). Plasma homocysteine concentrations change with vitamin B-6 depletion and repletion in young women. Nutr Res, 18:975.

- Ubbink, J.B., van der Merwe, A., Delport, R., Allen, R.H., Stabler, S.P., Riezler, R., Vermaak, W.J. (1996). The Effect of a Subnormal Vitamin B-6 Status on Homocysteine Metabolism. J Clin Invest, 98:177.

- Liao, D., Tan, H., Hui, R., Li, Z., Jiang, X., Gaubatz, J., Yang, F., Durante, W., Chan, L., Schafer, A.I., Pownall, H.J., Yang, X., Wang, H. (2006). Hyperhomocysteinemia decreases circulating HDL by inhibiting apoA-I protein synthesis and enhancing HDL-C clearance. Circ Res, 99:598.

- McKinley, M.C., McNulty, H., McPartlin, J., Strain, J.J., Pentieva, K., Ward, M., Weird, D.G., Scott, J.M. (2001). Low-dose vitamin B-6 effectively lowers fasting plasma homocysteine in healthy elderly persons who are folate and riboflavin replete. Am J Clin Nutr, 73:759.