Cellular Health and Aging

Cellular Health and Aging

Aging is an inevitable process that people wish to accomplish as healthfully as possible, and centuries of observation and study have led to important advances in understanding the mechanisms involved. Modern researchers are spending a bulk of their time trying to unravel the web of interactions associated with repair processes that might slow or break down over time, focusing much attention on the role of mitochondria in aging. Exciting discoveries that illuminate modifiable factors for maintaining mitochondrial health are uncovering dietary components that can exert some control over the aging process.

Mitochondria & Cellular Aging

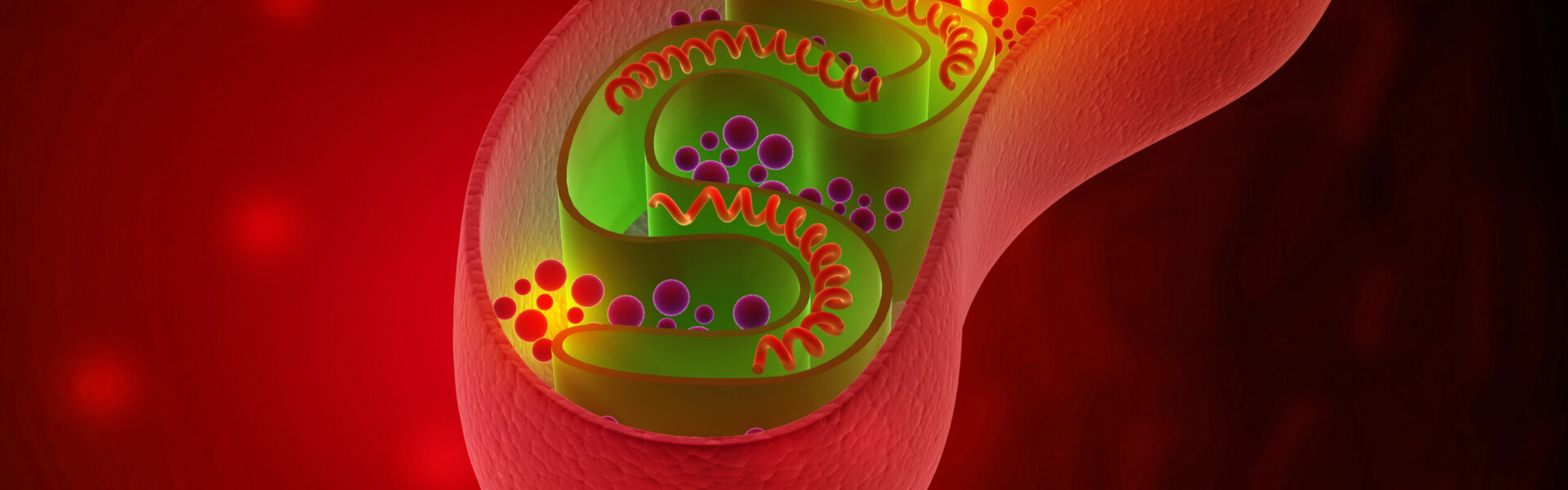

Mitochondria are intracellular structures found in most cells of the body. They are known most prominently for their role in converting energy from food into the chemical energy of the cell – adenosine triphosphate (ATP) – but they are also involved in cell signaling and controlling the lifecycle of the cell.1 ATP synthesis results in the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can be damaging to cells, tissues, and the mitochondrion itself. However, ROS also serve a function in cell signaling, so eliminating ROS entirely is not the goal. Key strategies are emerging that both balance ROS with endogenous defenses and activate enzymes involved in clean-up and repair. Current evidence is pointing to the role of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) and sirtuin proteins as major players in these strategies, which also have anti-aging effects.

Sirtuins are a family of enzymes that play an important role in cellular homeostasis and genetic repair. They were first studied for their ability to mimic calorie restriction (CR) – a documented means of prolonging lifespan in animal models. Sirtuins are activated through an increase in cellular levels of NAD+, and they are numbered one through seven (e.g. SIRT1, SIRT2, etc.). SIRT1 is important for maintaining genetic stability by removing acetyl groups from proteins called histones, which help keep DNA organized. SIRT3 has actions that are specific to the mitochondria. There is significant research interest surrounding methods for activating these enzymes for anti-aging benefits, including those that increase sirtuin activity directly and those that increase NAD+ levels. A decrease in NAD+ levels has been associated with factors associated with aging.2

What is CoQ10?

One important substance for upregulating sirtuin enzymes is Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10). CoQ10 is a lipid soluble molecule found in every cell of the body, concentrated in the inner membrane of the mitochondria. It is involved in energy production through its role in the electron transport chain (ETC). It is protective of the mitochondrial membrane via both its direct antioxidant capacity and its role in upregulating endogenous antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione (GSH). CoQ10 supplementation increases the activity and total number of mitochondria in tissues and shows benefit against several age-related diseases including cardiovascular disease, diabetes and neurodegenerative disorders.3, 4 These effects have been associated with the role of CoQ10 in activating SIRT1, SIRT3, and genetic transcription factors involved in both the biogenesis of new mitochondria and the production of SOD and GSH. A 2017 meta-analysis of studies covering 2149 patients with heart failure found that CoQ10 supplementation increased exercise capacity and decreased overall mortality by 31 percent.5

Polyphenols & Cellular Aging

Polyphenols are a group of phytonutrients found predominantly in fruits, vegetables, herbs, and seeds. Volumes of research exist highlighting polyphenols’ antioxidant and protective effects, which are now understood to involve the activation of sirtuins. Resveratrol is a polyphenol found in grapes, wine, peanuts, cocoa, pomegranate, and various berries (e.g. blueberries, cranberries and raspberries). Along with resveratrol’s action in upregulating endogenous antioxidants (e.g. SOD and GSH), it has been found to specifically activate SIRT3. SIRT3 exerts anti-aging influence by helping to activate processes that encompass damaged mitochondria and eliminate them (a process called mitophagy).6 Mitophagy results in a reduction of waste products and plays an important role in preventing age-related disorders.7

Fungi & Cellular Aging

Cordyceps is a genus of fungi used extensively in Chinese medicine as a tonic and health supplement, and many studies have shown effects against age-related diseases. Studies have shown effectiveness against tumors, diabetic renal injury, and neurodegeneration [8]. One study published in 2017 found cordyceps treatment to influence whole-body health through its action in promoting cell survival through mitophagy. The action was attributed to SIRT3 activation which was upregulated in all tissues studied except the central nervous system (CNS). Interestingly, the CNS of treated subjects still benefitted from greater protection possibly due to the enhanced blood supply with lower levels of waste products from surrounding tissues.8

American Ginseng & Cellular Aging

Herbal tonics have been used for centuries to maintain health and stamina, and modern research is supporting their use to prevent processes associated with aging. In Chinese medicine American Ginseng (panax quinquefolium) is known for its cooling and moistening qualities and the active components – ginsenosides – have been shown to have antioxidant, anti-aging, anti-cancer, adaptogenic, and other health promoting effects.9, 10 They appear to affect cellular viability by regulating mitochondrial processes such as energy metabolism, mitophagy, and apoptosis. One ginsenoside – Rb1 – has been shown to retard the aging process in mice.11 In rat cell studies, Rb1 activated the pathway associated with increasing NAD+ and activating SIRT3.12

Wheat Germ & Cellular Aging

Long known for its nutrient density and health benefits, wheat germ may soon add anti-aging effects to its resume. Wheat germ is the highest known food source of spermidine which shows the ability to mimic longevity effects associated with calorie restriction (i.e. upregulating sirtuins, inducing autophagy and increasing mitochondrial biogenesis).13 Whole blood spermidine levels decrease with aging but seem to be maintained in those with the longest lifespans (nonagenarians and centenarians).14 Spermidine supplementation in animal models has shown the ability to extend life span and improve cognition, and epidemiological evidence shows a decrease in all-cause mortality for subjects in the highest third of spermidine intake when compared to those in the lowest third.15-17 While spermidine is generally synthesized in sufficient quantities while one is young, the consumption of foods such as wheat germ may prove to be important dietary components for healthful aging later in life.

As scientists start to understand the mechanisms involved in aging, they are uncovering the importance of maintaining NAD+ levels and regulating sirtuins. These substances seem to be at the foundation of building, repairing, and maintaining healthy mitochondria and supporting the development and maintenance of healthy cells and tissues. The science on these mechanisms is still young, but while it continues to emerge it is empowering to know that researchers have preliminary evidence of the molecular actions involved in some time-tested nutrients and herbs.

- McBride, H.M., Neuspiel, M., & Wasiak, S. (2006). Mitochondria: more than just a powerhouse. Current Biology. 16(14): R551–60. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.054

- Zhang. M., & Ying, W. (2019). NAD+ deficiency is a common central pathological factor of a number of diseases and aging: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Antioxid Redox Signal, 30(6):890‐905. doi:10.1089/ars.2017.7445

- Luo, K., Yu, J.H., Quan, Y., et al. (2019). Therapeutic potential of coenzyme Q10 in mitochondrial dysfunction during tacrolimus-induced beta cell injury. Sci Rep, 9(1):7995. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-44475-x

- Tian, G., Sawashita, J., Kubo, H., et al. (2014). Ubiquinol-10 supplementation activates mitochondria functions to decelerate senescence in senescence-accelerated mice. Antioxid Redox Signal, 20(16):2606‐2620. doi:10.1089/ars.2013.5406

- Lei, L., & Liu, Y. (2017). Efficacy of coenzyme Q10 in patients with cardiac failure: a meta-analysis of clinical trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord, 17(1):196. doi:10.1186/s12872-017-0628-9

- Das, S., Mitrovsky, G., Vasanthi, H.R., & Das, D.K. (2014). Antiaging properties of a grape-derived antioxidant are regulated by mitochondrial balance of fusion and fission leading to mitophagy triggered by a signaling network of Sirt1-Sirt3-Foxo3-PINK1-PARKIN. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2014:345105. doi:10.1155/2014/345105

- Markaki, M., Palikaras, K., & Tavernarakis, N. (2018). Novel insights into the anti-aging role of mitophagy. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol, 340:169‐208. doi:10.1016/bs.ircmb.2018.05.005

- Takakura, K., Ito, S., Sonoda, J., et al. (2017). Cordyceps militaris improves the survival of Dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rats possibly via influences of mitochondria and autophagy functions. Heliyon, 3(11):e00462. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2017.e00462

- Hadady, L. (1996). Asian health secrets. Three Rivers Press.

- Kim, Y.J., Zhang, D., & Yang, D.C. (2015). Biosynthesis and biotechnological production of ginsenosides. Biotechnology Advances, 33 (6, Part 1): 717–735. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.03.001

- Shujie, Y., Hui, X., Yanlei, G., Xiaoxian, Q., Xiaojuan, Z., Huabing, Y., Mingzhu, Y., & Hongtao, L. (2020). Ginsenoside Rb1 retards aging process by regulating cell cycle, apoptotic pathway and metabolism of aging mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112746

- Fan, C., Ma, Q., Xu, M., et al. (2019). Ginsenoside Rb1 sttenuates high glucose-induced oxidative injury via the NAD-PARP-SIRT axis in rat retinal capillary endothelial cells. Int J Mol Sci, 20(19):4936. doi:10.3390/ijms20194936

- Kazuhiro, N., Ritsuko, S., Keiko, K., & Kazuei, I. (2006). Decrease in polyamines with aging and their ingestion from food and drink. Journal of Biochemistry, (1):81. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsovi&AN=edsovi.00004606.200601000.00010&site=eds-live

- Pucciarelli, S., Moreschini, B., Micozzi, D., et al. (2012). Spermidine and spermine are enriched in whole blood of nona/centenarians. Rejuvenation Res, 15(6):590‐595. doi:10.1089/rej.2012.1349

- Eisenberg, T., Abdellatif, M., Schroeder, S., et al. (2012). Cardioprotection and lifespan extension by the natural polyamine spermidine. Nat Med, 22(12):1428‐1438. doi:10.1038/nm.4222

- Pekar, T., Wendzel, A., Flak, W., et al. (2020). Spermidine in dementia : Relation to age and memory performance. Wien Klin Wochenschr, 132(1-2):42‐46. doi:10.1007/s00508-019-01588-7

- Kiechl, S., Pechlaner, R., Willeit, P., et al. (2018). Higher spermidine intake is linked to lower mortality: a prospective population-based study. Am J Clin Nutr, 108(2):371‐380. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqy102