Prebiotics, Probiotics, and other "Biotics"

Prebiotics, Probiotics, and Other “Biotics”

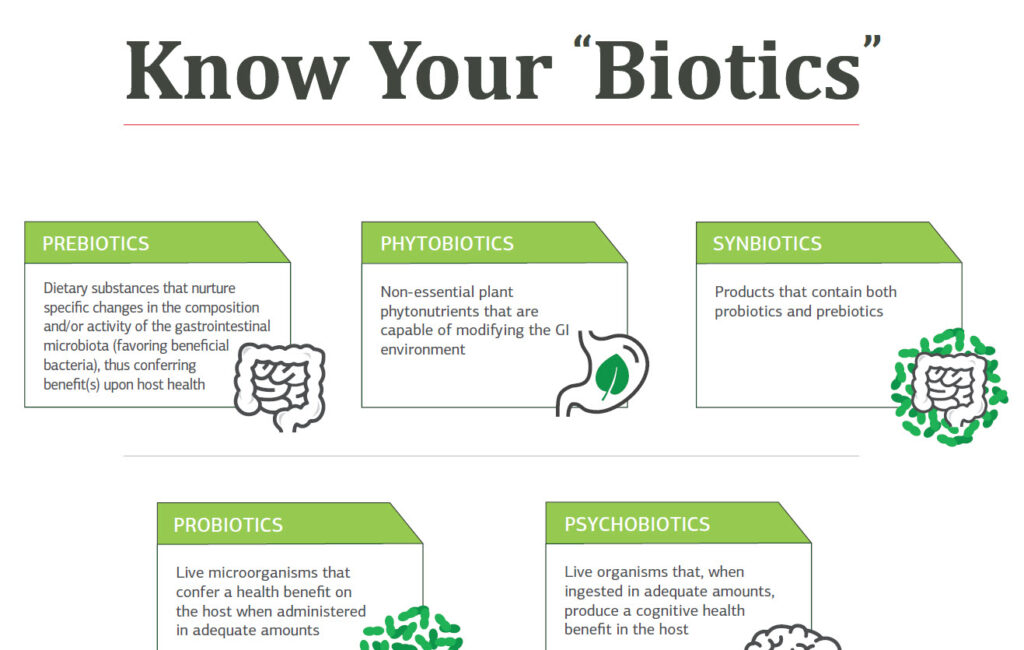

There are many different “biotic” products on the market, and it can be hard to know the difference between them. These products are designed to support the billions of microbes that live in the human body, each with unique characteristics and functioning via different mechanisms. The microbes in the digestive tract are commonly referred to as the gut microbiome, and they play essential roles in human health, from regulating the immune system to producing vitamins the body needs. Providing proper support to these microbes is important for good nutrition and health.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are dietary substances used selectively by microorganisms that nurture specific changes in the composition and/or activity of the gastrointestinal (GI) microbiota.1,2 Prebiotics favor beneficial bacteria, resulting in benefits for the health of the host. Clinical studies have shown a benefit with taking prebiotics and improvement in GI systems for patients with irritable bowel disease.2 Examples of prebiotics include non-digestible carbohydrates, polyphenols, and polyunsaturated fatty acids although many of the clinical studies investigating effects of prebiotics have focused on non-digestible oligosaccharides.2

Modifications induced by prebiotics affect specific strains of bacteria and the changes are not always easy to predict.1 One mechanism by which prebiotics exert beneficial effects is by increasing the production of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs). SCFAs provide energy to the intestinal cells, stimulate differentiation and proliferation of colonocytes, decrease the pH of the colon, and inhibit the growth and activity of pathogenic bacteria.2 Prebiotics also positively affect the GI microbiome by selectively promoting the growth of beneficial species, which in turn thwart the growth of pathogenic species through various mechanisms including antimicrobial substance production.1

Probiotics

Probiotics are live microorganisms that confer a health benefit on the host. Probiotics must be administered in adequate amounts for the microorganisms to be able to colonize and provide benefits.2 Because probiotic products contain living microorganisms, certain criteria must be met: they should be recognized as safe for human consumption, stay viable during preparation, and able to resist gastric and intestinal enzymes in order to reach their final destination in the GI tract.2 Similar to prebiotics, the mechanism of action of probiotics is strain-specific and is also influenced by the dose and components used to produce the probiotic.1 Some mechanisms of action include directly interacting with other microbes, inducing immune activation signaling via cytokine production and improving mucus secretion.2

Probiotics are relatively well studied and have demonstrated very promising results. Clinical studies have confirmed beneficial effects of probiotics on gastrointestinal diseases including irritable bowel syndrome as well as on other diseases including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.1 Probiotics have also been studied for their anti-carcinogenic, anti-oxidative, anti-aging, and antimicrobial actions as well as the ability to alleviate lactose intolerance, enhance immune function.3

Synbiotics

Synbiotics are products that contain both probiotics and prebiotics. The combination of prebiotic and probiotic components may have a synergistic effect by improving the chance of survival of the probiotic in the GI tract.1 Prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics have been found to alleviate intestinal inflammation due to their effects on intestinal ecology, intestinal homeostasis, and immune system homeostasis.2 Mechanistically, synbiotics are able to influence the composition of microbiota as well as increase production of SCFAs and modulate the immune system.2

Postbiotics

A postbiotics is a preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers a health benefit on the host.2-4 Postbiotics are complex mixtures of metabolic products or secreted components of probiotics such as enzymes, proteins, SCFAs, vitamins, amino acids, peptides, surface proteins, and organic acids.3 Many aspects of postbiotics remain to be studied, but current research is promising regarding their safety and efficacy. While it may seem counter-intuitive to use postbiotics to support the microbiome, evidence suggests that the viability of bacteria is not essential to the benefits that arise from probiotics.2 The benefits of postbiotics are related to their antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory functions and they are easier to produce and store due to their inanimate nature.2

Phytobiotics

Phytobiotics are non-essential plant phytonutrients that can modify the GI environment. They are most commonly used in feed animals as a replacement for antibiotic growth promoters.5 In humans, phytobiotics include medicinal herbs that upregulate the growth of beneficial species and possess anti-microbial actions including oregano, garlic, rosemary, thyme, and clove.6

Psychobiotics

Psychobiotics are live microorganisms that produce a cognitive health benefit in the host. Similar to probiotics, psychobiotics must be ingested in adequate amounts in order to have an effect. Use of psychobiotics has been found to result in participants self-rating as “happy” rather than depressed as well as decrease the number of self-reported negative moods and distress.7 The psychophysiological effects of psychobiotics in humans are categorized into three main areas:7

- Psychological effects on emotional and cognitive processes

- Systemic effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, glucocorticoid stress response, and inflammation

- Neural effects on neurotransmitters and proteins including GABA and glutamate

The precise mechanisms of action are not known, but studies have begun to piece together possible relationships linking psychobiotics to improved cognitive function. Prebiotics and probiotics can increase the production of SCFAs which interact with other GI components to increase secretion of gut hormones. The SCFAs and gut hormones enter circulation and migrate to the central nervous system where they can exert a psychophysiological effect.7 Psychobiotics also increase neurotransmitter synthesis in the gut including dopamine, serotonin, and GABA which modulate neurotransmission. Finally, communication between the brain and gut via the vagus nerve also is an additional mechanism through which psychobiotics may be working.7

There are still unanswered questions about the microbiome, including what constitutes a “healthy” microbiome, but it is clear that the microbiome is unique to each person based on their exposure to diet, medications, and toxins. Utilizing the optimal mix of “biotics” can help individuals target their specific needs and unique microbiome in order to gain the most health benefits.

KNOW YOUR BIOTICS

The microbes in the digestive tract are known collectively as the gut microbiome and can play multiple roles in human health, starting before birth and continuing throughout life.

- Markowiak, P., Śliżewska, K. (2017). Effects of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics on Human Health. Nutrients, 9(9):1021-1050.

- Maioli, T.U., Trindade, L.M., Souza, A., Torres, L., Andrade, M.E.R., Cardoso, V.N., Generoso, S.V. (2022). Non-pharmacologic strategies for the management of intestinal inflammation. Biomed Pharmacother, 145:112414.

- Nataraj, B.H., Ali, S.A., Behare, P.V., Yadav, H. (2020). Postbiotics-parabiotics: the new horizons in microbial biotherapy and functional foods. Microb Cell Fact, 19(1):168-189.

- Salminen, S., Collado, M.C., Endo, A., Hill, C., Lebeer, S., Quigley, E.M.M., Sanders, M.E., Shamir, R., Swann, J.R., Szajewska, H., Vinderola, G. (2021). The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nat Rev Gastro Hepat, 18(9):649-667.

- Gheisar, M.M., Kim, I.H. (2018). Phytobiotics in poultry and swine nutrition- a review. Ital J Anim Sci, 17(1):92-99.

- Parham, S., Kharazi, A.Z., Bakhesheshi-Rad, H.R., Nur, H., Ismail, A.F., Sharif, S., Ramakrishna, S., Berto, F. (2020). Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Antiviral Properties of Herbal Materials. Antioxidants, 9(12):1309-1344.

- Sarkar, A., Lehto, S.M., Harty, S., Dinan, T.G., Cryan, J.F., Burnet, P.W.J. (2016). Psychobiotics and the Manipulation of Bacteria-Gut-Brain Signals. Trends Neurosci, 39(11):763-781.