The Power of Synergy and Bioavailability in the Whole Food Matrix

The nutrition label does not tell the whole story of nutrient content, bioavailability, and utilization in the body. Nutrients consumed as part of a natural, whole food matrix provide benefits that go beyond those of individual vitamins and minerals. The combination of nutrients, bioactive compounds, and phytochemicals found in the whole food matrix can enhance nutrient absorption, increase bioavailability, and interact synergistically to provide health benefits to the body.

What is the Whole Food Matrix?

With the discovery of vitamin C, scientists began searching for the existence of and function of single nutrients.1–3 These discoveries led to major advancements in human health, but they also brought about a reductionist view of nutrition at times.

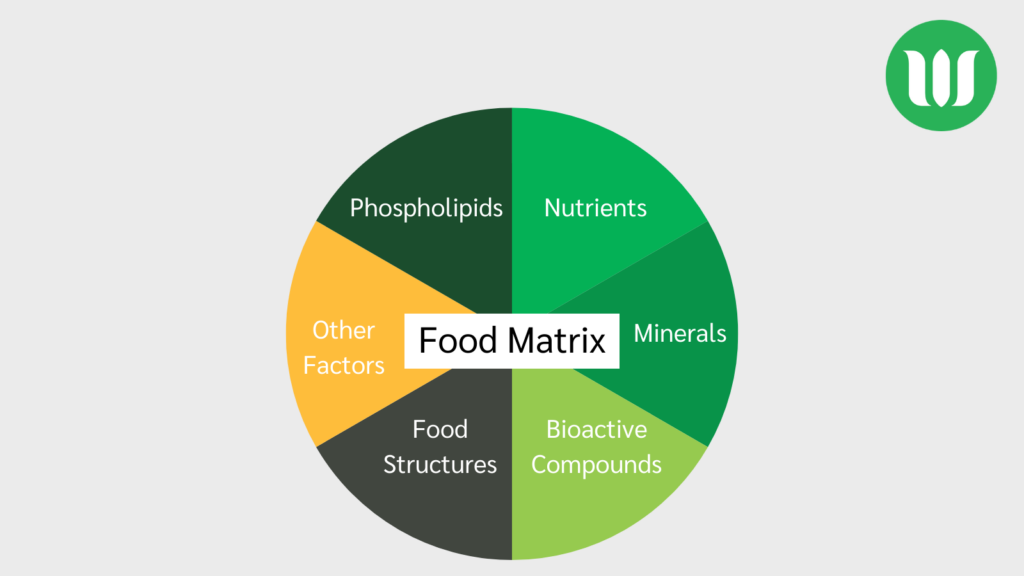

The fact is humans do not eat single nutrients at prescribed doses. Rather, they consume foods that consist of a complex matrix of nutrients, minerals, bioactive compounds, food structures, phospholipids, and other factors like prebiotics.3

| An overly simplistic view of nutrition fails to account for the whole food matrix, a concept that encompasses the overall chemical dynamics of food, including how various components are structured and interact, including the texture, form, and microstructure of food.4,5 |

Elements of the food matrix affect the digestion and absorption of nutrients and scientific evidence indicates that consuming nutrients as part of a natural, whole food matrix can enhance overall health and prevent illness.5

Health Benefits of Consuming Whole Foods

Plants and animals create systems that allow them to grow, survive, and maintain biological processes.2 Living tissue is complex. It contains components that have some degree of biological activity and can benefit plants and animals themselves while also providing humans with high quality nutrition when consumed in whole food form.2 For example, nuts contain unsaturated fats as well as antioxidants that help stabilize them. It is these antioxidants that also provide benefits to humans when consumed.6

Whole foods promote multiple aspects of human health, including boosting antioxidant status, supporting healthy inflammation, modulating metabolic processes, and enhancing the immune response.7 Their beneficial effects are even more pronounced when they replace ultra-processed foods, which are particularly unhealthy and negatively influence metabolic health, long-term dietary behaviors, satiety signaling, and food reward systems.8

Whole foods contain essential vitamins, minerals, and macronutrients that support overall health and help avoid nutrient deficiencies. Foods in their whole food matrix may enhance the bioavailability of these nutrients, increasing absorption and utilization throughout the body.

Because many factors affect nutrient digestion and absorption, the numbers on the nutrition label do not always align with actual bioavailability within the body. However, consuming nutrients in the right proportions as part of the whole food matrix can enhance absorption and bioavailability, potentially resulting in increased levels compared to what a processed version of the same food can be absorbed.

The Role of Bioactive Compounds

Within the whole food matrix, there are also bioactive compounds such as hormones, sterols, enzymes, phytonutrients, and signal transducers, all of which can affect cells in the body when they are absorbed and circulated throughout the body.2

Often, these nutrients and bioactive compounds in the whole food matrix interact synergistically, resulting in a greater, or different, action compared to that of single nutrients.6 Together, the whole food matrix and its synergistic effects allow for more thorough digestion and absorption, enhancing the absorption of other nutrients.6

For example, polyphenols can inhibit the actions of enzymes that break down starches, including alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase, which slow the digestion of carbohydrates and support overall blood glucose metabolism.9

Whole Food Matrix Clinical Considerations

Enhanced bioavailability and nutrient synergy from the whole food matrix can impact many areas of health and wellness. For example, athletes who consume protein within the context of a whole food matrix may experience enhanced recovery and increased muscle mass synthesis.

In one study, post-exercise muscle protein synthesis was more strongly stimulated by whole eggs compared to egg whites.10 Egg whites offer a leaner source of protein, however, a whole egg in the food matrix also includes lipids, vitamins, and minerals that result in an interaction within the body, and possibly muscle tissue, that creates an enhanced response.7

For the general population, consuming nutrients as a part of the whole food matrix can reduce the risk of diseases including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and stroke, as well as support day-to-day and long-term health.1

Clinical Study Limitations

Studying the effects of the whole food matrix on health can be challenging. Clinical studies attempt to hold as many variables constant as possible, which is challenging with whole food studies because foods are complex items with distinct textures and tastes. This makes it nearly impossible to control every variable and mask participants to avoid a placebo effect.2

However, studies have confirmed differences in health effects when foods are consumed as part of the whole food matrix or when consumed as an isolated nutrient. For example, fiber from whole grain sources reduced mortality in women but fiber from refined grain did not.11 These results demonstrate that it is not simply about eating fiber from any source to obtain benefits, but rather consuming fiber alongside phytonutrients and other food matrix components.

Similar results have been seen for other whole foods, including pomegranates, cruciferous vegetables, and various fruits.2

Implementation of Whole Food Strategy

As a part of a whole food nutrition strategy that aims to harness the power of the whole food matrix, it is essential to look beyond the label.

While the nutrition facts label can provide useful information, it does not offer a complete picture of the healthy and unhealthy attributes of food.1 For example, the saturated fat commonly found in dairy products may indicate an unhealthy food choice on the label. However, multiple studies have confirmed that dairy products, both low and full fat, do not lead to significant weight gain, poor cardiovascular health, or type 2 diabetes, which is likely due to the whole food matrix.3

Beyond the fat and protein content, milk contains bioactive components as part of the whole food matrix that affects how other macronutrients and micronutrients are digested, absorbed, and utilized in the body.1,3,5

Whole Food Supplementation

Whole foods remain the ideal way to get nutrients, but many people fall short of recommended intakes. For individuals who struggle to obtain all essential nutrients through food alone, whole food supplements can be a useful tool to increase nutrient intake and avoid nutrient deficiencies while still reaping the benefits of the whole food matrix.

When considering whole food supplementation, it is important to evaluate:

- The type of supplement, including form, nutrient content, and source of nutrients

- Any processing of the ingredients

- The extent to which nutrients are delivered in their whole food matrix

A supplement containing synthetic vitamins may offer a higher dose of a nutrient, but if the body cannot properly absorb that specific form, it is less likely to provide the desired benefits to the body. If, however, a whole food supplement contains a slightly lower dose, but is more bioavailable or contains additional isolated micronutrients, that may be the more appropriate option to achieve the sought after outcome.

To best support health and reduce disease risk, dietary intake of essential nutrients through whole foods is best. The whole food matrix provides a host of health benefits, including increasing nutrient bioavailability and enhancing the effects of nutrients and bioactive compounds through synergistic activity.

For individuals who need to fill in gaps in their diet, whole food supplements can deliver essential nutrients in a whole food matrix. Together, whole foods and whole food supplements that are as close as possible to the natural form provide the most functional benefits for the body.

- Miller, G.D., Ragalie-Carr, J., Torres-Gonzalez, M. (2023). Perspective: Seeing the Forest Through the Trees: The Importance of Food Matrix in Diet Quality and Human Health. Adv Nutr, 14(3):363.

- Jacobs, D.R., Tapsell, L.C. (2007). Food, Not Nutrients, Is the Fundamental Unit in Nutrition. Nutr Rev, 65(10):439.

- Mozaffarian, D. (2019). Dairy Foods, Obesity, and Metabolic Health: The Role of the Food Matrix Compared with Single Nutrients. Adv Nutr, 10:917S.

- Moughan, P.J. (2020). Holistic properties of foods: a changing paradigm in human nutrition. J Sci Food Agric, 100(14):5056.

- Cifelli, C.J. (2021). Looking beyond traditional nutrients: the role of bioactives and the food matrix on health. Nutr Rev, 79(Suppl 2):1.

- Jacobs, D.R., Gross, M.D., Tapsell, L.C. (2009). Food synergy: an operational concept for understanding nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr, 89:1543S.

- Burd, N.A., Beals, J.W., Martinez, I.G., Salvador, A.F., Skinner, S.K. (2019). Food-First Approach to Enhance the Regulation of Post-exercise Skeletal Muscle Protein Synthesis and Remodeling. Sports Medicine, 49(Suppl 1):S59.

- Juul, F., Vaidean, G., Parekh, N. (2021). Ultra-processed Foods and Cardiovascular Diseases: Potential Mechanisms of Action. Adv Nutr, 12:1673.

- Kan, L., Oliviero, T., Verkerk, R., Fogliano, V., Capuano, E. (2020). Interaction of bread and berry polyphenols affect starch digestibility and polyphenols bio-accessibility. J Funct Foods, 68:103924.

- Van Vliet, S., Shy, E.L., Sawan, S.A., et al. (2017). Consumption of whole eggs promotes greater stimulation of postexercise muscle protein synthesis than consumption of isonitrogenous amounts of egg whites in young men. Am J Clin Nutr, 106(6):1401.

- Jacobs, D.R., Pereira, M.A., Meyer, K.A., Kushi, L.H. (2000). Fibers from whole grains, but not refined grains, is inversely associated with all-cause mortality in older women: the Iowa women’s health study. J Am Coll Nutr, 19(Suppl 3):326S.