Nutritional & Botanical Support For GLP-1 Activity

What is GLP-1?

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) is a naturally occurring incretin hormone produced in the gut that plays a key role in regulating blood sugar levels, appetite and satiety. GLP-1 is released in response to food intake, and has several important functions, including stimulating insulin release, suppressing glucagon release, slowing gastric emptying, and reducing appetite. Impaired GLP-1 secretion is considered a significant component of the pathology of overweight and obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes, as individuals with these conditions often exhibit reduced GLP-1 release in response to food intake compared to healthy individuals.1 Several factors can cause reduced GLP-1 secretion, including overweight and obesity, sleep deprivation, chronic stress, and certain gut conditions, leading to significant dysregulation of appetite, insulin sensitivity, glucose regulation, and even cardiovascular and neurological processes.

GLP-1 Agonist Medications

Targeting GLP-1 has become a primary area of focus for cardiometabolic health, including weight management. GLP-1 agonist drugs, which are synthetic versions of the naturally occurring GLP-1 hormone, have been used for decades in the treatment and management of Type II Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM). Recently, these GLP-1 agonists have made their way into the marketplace as miracle weight loss drugs because they suppress appetite and slow gastric emptying, which helps prolong the sense of fullness after a meal and makes it easier to remain in a significant caloric deficit.

Many individuals using these medications describe their effects as turning off the ‘food noise,’ or the constant thoughts about food that make adhering to dietary changes so difficult, particularly for those with food addictions or a history of overeating. While they may seem like a dream come true for many individuals who have struggled to lose weight, they are not without their own inherent risks and pitfalls.

The main concerns with GLP-1 agonist drugs include:

- GI side effects (nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, constipation, abdominal pain)

- High out-of-pocket cost for those who do not quality under insurance

- Risk of inadequate nutrition (reduced intake + insufficient nutrition counseling)

- Significant loss of muscle mass & bone density

- High discontinuation rates (with lost weight regained)

- Limited public & clinician knowledge on importance/implementation of nutrition and lifestyle changes

Side Effects and Costs of GLP-1 Medications

The use of GLP-1 drugs has been associated with numerous side effects, ranging from mild to severe. Common side effects include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, headaches and injection site reactions (redness, swelling, irritation).2 Less common but significantly more severe side effects have been documented, including gastroparesis, pancreatitis, kidney complications, the development of arthritis, vision loss and possibly even thyroid cancer;2-4 the risk for experiencing the more seriously complications seems to be associated with longer-term use of the medications.

In addition to the possible health risks associated with the use of GLP-1 drugs, these therapies are associated with a high out-of-pocket cost for individuals who do not qualify for their use through insurance, such as those wanting to lose weight without falling into the obesity or diabetes categories. Programs that offer subscription-based medication services often cost upwards of $300 per month, and these non-FDA approved compounded GLP-1 medications raise serious concerns due to variability in dosage, potential for harmful additives, and lack of rigorous safety and efficacy testing.

Natural Alternatives and Adjunctive Support with Botanicals and Nutrients

Certain nutrients and botanicals have demonstrated GLP-1 agonist activity, and are not associated with the complications often seen with pharmaceutical GLP-1 drug use. Nutritional interventions with protein, satiating slow-release carbohydrates and fiber, as well as herbs that regulate digestion and insulin response all offer an alternative to pharmaceutical GLP-1 intervention, or support in helping patients transition off of long-term use of the drugs. Additionally, many of these herbs and nutrients may also offer protective or mitigating effects against the undesirable side effects experienced with GLP-1 drugs.

Bitter Herbs and Foods with GLP-1 Agonist Activity

Bitter foods and herbs, like arugula, dandelion leaf and root, gentian root, burdock root and many others, have a long history of use for supporting digestive processes. The taste of bitter helps to stimulate digestive secretions, support peristalsis and encourage regular elimination. Modern research into bitter compounds, such as alkaloids, has shown that these phytochemicals in foods and herbs target bitter taste receptors, specifically TAS2Rs, found throughout the digestive system.8 When bitter compounds are detected, these TAS2Rs trigger neural pathways that influence not just digestive capacity but behaviors as well, including diet choice.

Many herbalists use the taste of bitter to combat sugar addictions, noting that the taste of bitter has been practically eradicated from the American diet and replaced with an overabundance of sweet tastes- a practice supported by scientific research. Preclinical research shows that bitter compounds act through an extracellular odorant binding protein to inhibit sweet-responsive neurons and block the response to sweet taste,9 making bitter herbs an important therapeutic tool in modifying dietary choices.

TAS2Rs, particularly in enteroendocrine cells, are involved in the release of GLP-1. Activation of these receptors by bitter compounds stimulates GLP-1 secretion, which can lead to various effects like increased satiety, improved insulin sensitivity and reduced blood sugar levels.10 Targeting these TAS2Rs with bitter compounds targeting extra-oral bitter taste receptors could be a strategy to influence gastrointestinal motility, and potentially impact hunger signals, similar to the use of pharmaceutical GLP-1 agonists.

In addition to the interplay with GLP-1 activity, these bitter and aromatic herbs can help to mitigate many of the undesirable side effects experienced by many patients using GLP-1 therapies, including constipation and nausea.

Members of the Gentiana family, widely known for their profoundly bitter taste, have been shown to stimulate GLP-1 release and normalize blood glucose.11 In one clinical trial, the secoiridoids found in gentian, which are the compound responsible for that bitter taste, demonstrated both a higher response of GLP-1 and a significantly reduced appetite, evidenced by a 30% lower energy intake over the post-lunch period.12

Parthenolide, a bitter compound found in the feverfew plant, has also shown promise in addressing obesity and related complications. In one study, the phytochemical inhibited both obesity and obesity-related inflammation, evidenced by a reduction in body mass and white adipose tissue as well as the downregulation of NF-κB and MAPKs.13

Wormwood and tangerine peel, while not directly related to GLP-1 activity, have a long history of use in supporting digestive processes and may be beneficial in augmenting the glucose-lowering and anti-obesity effects of GLP-1 agonists. Bioflavonoids found in citrus peels such as tangerine have been shown to suppress adipogenesis and adipocyte differentiation, as well as improve anthropometric measurements like waist circumference.14

In pre-clinical research, formulations of tangerine peel not only inhibited insulin resistance and reduced hepatic lipid accumulation, but also improved markers of intestinal integrity and improved microbiota dysbiosis.15 Both dysbiosis and impaired gut integrity have been strongly associated with the development of overweight, obesity and metabolic syndrome, and should be a key focus of therapeutic protocols either independent of or alongside GLP-1 agonist therapy in supporting weight management.

Ginger is one of the most well-known herbs for supporting digestion, and has a long history of use in the management of indigestion and nausea. In recent research, ginger, and its active compound gingerol, have shown potential in modulating GLP-1 activity, improving insulin response and managing blood glucose through a variety of pathways.

Pre-clinical research has shown that gingerol potentiates GLP-1 activity, and facilitates glucose uptake in skeletal muscles through increased activity of glycogen synthase 1 and enhanced cell surface presentation of GLUT4 transporters,16,17 proteins that play a central role in regulating blood glucose levels by facilitating the transport of glucose across the cell membrane. Ginger extract has even been shown to regenerate pancreatic islets, the cells responsible for producing insulin and glucagon that can become damaged with insulin resistance and Type II Diabetes.18 Importantly, decades worth of clinical studies have pointed to ginger’s efficacy in mediating nausea and vomiting,19 two of the most prominent side effects of GLP-1 therapy.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Omega-3 fatty acids, particularly the long-chain fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), support numerous physiological functions in the body, including the regulation of inflammation, modulation of immune function and support of cardiovascular health. The Western or Standard American Diet is deficient in omega-3 fatty acids, which in addition to contributing to the pathogenesis of cardiometabolic, neurodegenerative and autoimmune diseases,20 may have an impact on GLP-1 activity as well. There is increasing evidence that both EPA and DHA support insulin regulation and reduce the risk of developing T2DM.21-24 The Free Fatty Acid Receptor 1 (FFAR1) in the gut, activated by the intake of EPA and DHA, facilitates the glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells, while G-Protein Coupled Receptor 120 (GPR120) that regulates the secretion GLP-1 can also be upregulated by EPA and DHA intake.25 Research also suggests that EPA and DHA may act directly on the pancreas to improve insulin secretion.26

Certain GLP-1 agonist drugs have been associated with a significantly increased risk of depression and anxiety,27 highlighting an emerging need for complimentary therapies to support patient’s mental and emotional health while undergoing pharmaceutical GLP-1 therapy. EPA in particular has been shown to have a positive impact on mood regulation, particularly in the case of depression..28

Increasing EPA and DHA intake may offer patients the dual benefit of additional GLP-1 regulation as well as encouraging improved mental health parameters. EPA and DHA can be found in marine sources, including salmon, tuna, cod liver, calamari mackerel, sardines and even some types of algae, however supplementation is typically recommended to obtain therapeutic amounts when dietary intake of these sources is low.

Supporting Satiety and Maintaining Muscle Mass

Encouraging the feeling of satiety to minimize the drive to overconsume calories is a central focus for GLP-1 therapy, and can be part of a protocol alongside GLP-1 drugs or encouraged through nutrition and supplementation alone.

Protein and Weight-Bearing Exercise

Protein is considered to have the highest satiety rating of the macronutrients; this effect is linked to several mechanisms, including:

- triggering the release of leptin and peptide YY to signal a sensation of fullness and satiety29

- triggering the secretion of GLP-1 to increase feelings of satiety30

- slower digestion rate compared to other macronutrients

Adequate protein intake while in a caloric deficit, either through the use of GLP-1 medications or adhering to a lower calorie diet, is essential for helping to protect lean body mass. Both protein intake and the maintenance of muscle mass through diet and exercise are important for preserving overall metabolic rate and health. Protein has a higher thermic effect of food rating, meaning that the body burns more energy digesting protein than either fat or carbohydrates.

Muscle tissue is more metabolically active than fat, so it burns more calories at rest on a daily basis. Increasing or at least maintaining muscle mass through protein intake and weight bearing exercises during a weight loss program will support the maintenance of basal metabolic rate (BMR) and prioritize the loss of fat rather than muscle.

Fiber

It is important, however, not to compromise fiber intake in favor of adhering to a low calorie, high protein diet program. Dietary fiber intake is considered to be one of the most important aspects of not just digestive health, but cardiometabolic health as well.

Intake of water-soluble dietary fiber, including pectins, gums, fructans and some resistant starches, has been shown to have many similar effects to the goals of GLP-1 therapy, such as:

- regulating both short and long-term glycemic control

- improving insulin sensitivity

- lowering blood cholesterol

- reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease31,32

Both soluble and insoluble fibers also modulate microbiome composition and function, improving digestive health and supporting weight management. Pre-clinical and clinical research show a strong connection between fiber intake, microbiome health, and GLP-1 activity. Studies have indicated that prebiotic fiber such as inulin upregulate GLP-1 in models of obesity.33 Butyrate, a short chain fatty acid that is produced by gut bacteria from fermenting fiber, can stimulate the secretion of GLP-1 from intestinal L-cells.34

In human research, administration of prebiotic fiber has been associated with a significant decrease in hunger, significantly greater satiation after meals and increased plasma GLP-1 levels.35 One of the most attractive features of GLP-1 drugs is that they shut off the ‘food noise’ so many people experience that makes staying in a caloric deficit or even just changing food preferences so difficult. Targeting satiety, or the feeling of fullness, is a key therapeutic strategy for both nutritional interventions like increased fiber intake and GLP-1 agonists alike.

Constipation due to decreased gastric motility is one of the most experienced side effects of GLP-1 drugs. Fiber is well known for its ability to add bulk to and soften the stool, encouraging both peristalsis and bowel regularity.36 Because appetite reduction is common with GLP-1 agonists, and many individuals on GLP-1 therapies are counseled to prioritize protein and/or follow a ketogenic diet to support muscle maintenance during weight loss, fiber intake is often reduced significantly as fruits, vegetables and grains are eliminated.

In order to improve fiber intake during a caloric deficit with reduced appetite, prioritizing the highest-fiber food sources (avocado, chia seeds, pears, berries, legumes) alongside fiber supplementation will help to mitigate the constipation experienced with GLP-1 agonists while supporting the therapeutic goal of satiety and blood glucose regulation.

The recommended daily allowances (RDAs) for total fiber intake for men and women aged 19–50 are 38 gram/day and 25 gram/day, respectively.32 However many functional practitioners consider even this amount to be inadequate, and encourage working up to 35-50 g/daily depending on individual tolerance. For many individuals this may be challenging, so supplementing with whole-foods sources of fiber, including apple pectin, oat fiber, beet fiber, carrot fiber and psyllium husk can help address gaps in dietary fiber intake. Timing fiber intake, particularly soluble fiber, around meals can help to minimize postprandial glucose spikes by slowing down the absorption of glucose during digestion, leading to a more gradual rise in blood glucose and lasting feelings of satiety following meals.

Clinical Takeaways

As the prevalence of obesity, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and associated health complications continue to rise, targeting GLP-1 activity has emerged as a promising strategy in improving cardiometabolic health and encouraging sustainable weight loss. Pharmaceutical GLP-1 agonists offer many health benefits, however their high cost, potential side effects, and weight regain after discontinuation or the requirement for lifetime adherence are major deterrents for many individuals, and highlight the need for more accessible options with improved safety profiles.

Nutritional and botanical interventions, including bitter herbs, omega-3 fatty acids and targeted nutrient balance offer evidence-based alternatives to GLP-1 drugs, as well as opportunities to support those patients already using GLP-1 medications in mitigating side effects and augmenting their results. Nutritional therapies and herbs both improve GLP-1 activity and in many cases correct the numerous underlying contributors to metabolic dysfunction, through improving insulin sensitivity and satiety, supporting microbiome health and mitigating inflammation that can disrupt metabolic function. Incorporating nutrient- and herb- based interventions offer patients a safer, more integrated path towards improved metabolic health and weight management.

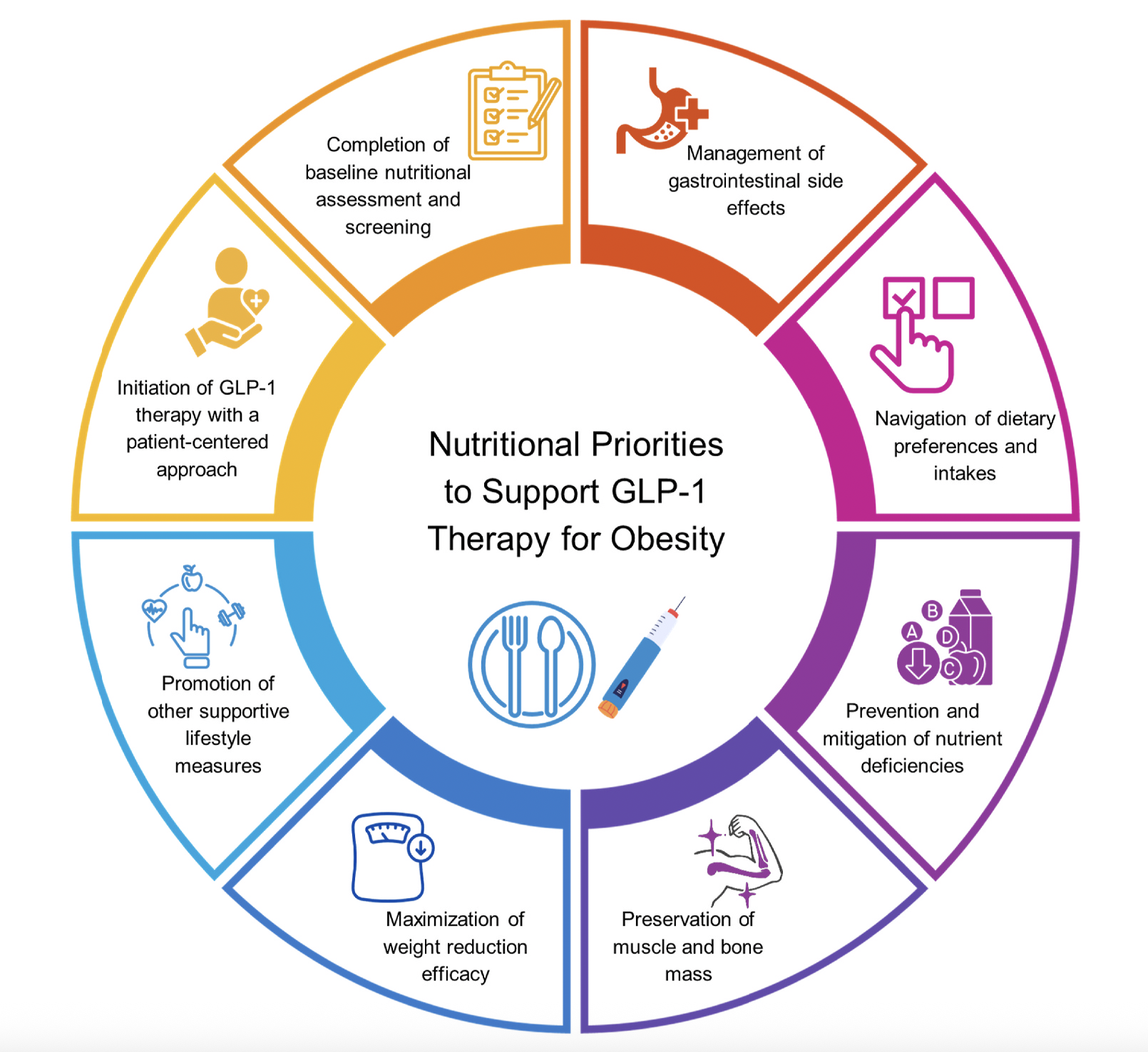

Key elements of nutritional priorities to support GLP-1 therapy for obesity

(A joint advisory from the American Society for Nutrition, the American College of Lifestyle medicine, the Obesity Medicine Association and the Obesity Society)

Did you know WholisticMatters is powered by Standard Process? Learn more about Standard Process’ whole food-based nutrition philosophy.

- Paternoster S, Falasca M. Dissecting the physiology and pathophysiology of glucagon-like peptide-1. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2018;9:584.

- Xie Y, Choi T, Al-Aly Z. Mapping the effectiveness and risks of GLP-1 receptor agonists. Nature Medicine. 2025/03/01 2025;31(3):951-962. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-03412-w

- Hathaway JT, Shah MP, Hathaway DB, et al. Risk of Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy in Patients Prescribed Semaglutide. JAMA Ophthalmology. 2024;142(8):732-739. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2024.2296

- Lisco G, De Tullio A, Disoteo O, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists and thyroid cancer: is it the time to be concerned? Endocr Connect. Nov 1 2023;12(11)doi:10.1530/ec-23-0257

- Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Davies M, et al. Weight regain and cardiometabolic effects after withdrawal of semaglutide: The STEP 1 trial extension. Diabetes Obes Metab. Aug 2022;24(8):1553-1564. doi:10.1111/dom.14725

- Abdullah Bin Ahmed I. A Comprehensive Review on Weight Gain following Discontinuation of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists for Obesity. J Obes. 2024;2024:8056440. doi:10.1155/2024/8056440

- Berg S, Stickle H, Rose SJ, Nemec EC. Discontinuing glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and body habitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews. n/a(n/a):e13929. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13929

- Wooding SP, Ramirez VA, Behrens M. Bitter taste receptors: Genes, evolution and health. Evol Med Public Health. 2021;9(1):431-447. doi:10.1093/emph/eoab031

- Lvovskaya S, Smith DP. A spoonful of bitter helps the sugar response go down. Neuron. Aug 21 2013;79(4):612-4. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2013.07.038

- Kok BP, Galmozzi A, Littlejohn NK, et al. Intestinal bitter taste receptor activation alters hormone secretion and imparts metabolic benefits. Molecular Metabolism. 2018/10/01/ 2018;16:76-87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2018.07.013

- Suh H-W, Lee K-B, Kim K-S, et al. A bitter herbal medicine Gentiana scabra root extract stimulates glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion and regulates blood glucose in db/db mouse. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2015/08/22/ 2015;172:219-226. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2015.06.042

- Mennella I, Fogliano V, Ferracane R, Arlorio M, Pattarino F, Vitaglione P. Microencapsulated bitter compounds (from Gentiana lutea) reduce daily energy intakes in humans. Br J Nutr. Nov 28 2016;116(10):1841-1850. doi:10.1017/s0007114516003858

- Rezaie P, Bitarafan V, Horowitz M, Feinle-Bisset C. Effects of Bitter Substances on GI Function, Energy Intake and Glycaemia-Do Preclinical Findings Translate to Outcomes in Humans? Nutrients. Apr 16 2021;13(4)doi:10.3390/nu13041317

- Lu K, Yip YM. Therapeutic potential of bioactive flavonoids from citrus fruit peels toward obesity and diabetes mellitus. Future Pharmacology. 2023;3(1):14-37.

- Zou J, Song Q, Shaw PC, Wu Y, Zuo Z, Yu R. Tangerine Peel-Derived Exosome-Like Nanovesicles Alleviate Hepatic Steatosis Induced by Type 2 Diabetes: Evidenced by Regulating Lipid Metabolism and Intestinal Microflora. Int J Nanomedicine. 2024;19:10023-10043. doi:10.2147/ijn.S478589

- Samad MB, Mohsin M, Razu BA, et al. [6]-Gingerol, from Zingiber officinale, potentiates GLP-1 mediated glucose-stimulated insulin secretion pathway in pancreatic β-cells and increases RAB8/RAB10-regulated membrane presentation of GLUT4 transporters in skeletal muscle to improve hyperglycemia in Lepr(db/db) type 2 diabetic mice. BMC Complement Altern Med. Aug 9 2017;17(1):395. doi:10.1186/s12906-017-1903-0

- Salaramoli S, Mehri S, Yarmohammadi F, Hashemy SI, Hosseinzadeh H. The effects of ginger and its constituents in the prevention of metabolic syndrome: A review. Iran J Basic Med Sci. Jun 2022;25(6):664-674. doi:10.22038/ijbms.2022.59627.13231

- Abbood MS, Al-Adsani AM, Al-Bustan SA. Ginger extract promotes pancreatic islets regeneration in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Bioscience Reports. 2025;45(03):171-184. doi:10.1042/bsr20241510

- Li Z, Wu J, Song J, Wen Y. Ginger for treating nausea and vomiting: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Int J Food Sci Nutr. Mar 2024;75(2):122-133. doi:10.1080/09637486.2023.2284647

- Simopoulos AP. The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomed Pharmacother. Oct 2002;56(8):365-79. doi:10.1016/s0753-3322(02)00253-6

- Djousse L, Biggs ML, Lemaitre RN, et al. Plasma omega-3 fatty acids and incident diabetes in older adults. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2011;94(2):527-533.

- Virtanen JK, Mursu J, Voutilainen S, Uusitupa M, Tuomainen T-P. Serum omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and risk of incident type 2 diabetes in men: the Kuopio Ischemic Heart Disease Risk Factor study. Diabetes care. 2014;37(1):189-196.

- Oh D. talukdar S, Bae eJ, Imamura t, Morinaga H, Fan W, li P, lu WJ, Watkins SM, Olefsky JM (2010) gPr120 is an omega-3 fatty acid receptor mediating potent anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing effects. Cell. 142:687-698.

- Ibrahim A, Rajkumar L, Acharya V. Dietary (n-3) long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids prevent sucrose-induced insulin resistance in rats. The Journal of nutrition. 2005;135(11):2634-2638.

- Hara T, Hirasawa A, Ichimura A, Kimura I, Tsujimoto G. Free fatty acid receptors FFAR1 and GPR120 as novel therapeutic targets for metabolic disorders. J Pharm Sci. Sep 2011;100(9):3594-601. doi:10.1002/jps.22639

- Albert BB, Derraik JGB, Brennan CM, et al. Higher omega-3 index is associated with increased insulin sensitivity and more favourable metabolic profile in middle-aged overweight men. Scientific Reports. 2014/10/21 2014;4(1):6697. doi:10.1038/srep06697

- Kornelius E, Huang J-Y, Lo S-C, Huang C-N, Yang Y-S. The risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidal behavior in patients with obesity on glucagon like peptide-1 receptor agonist therapy. Scientific Reports. 2024/10/18 2024;14(1):24433. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-75965-2

- Liao Y, Xie B, Zhang H, et al. Efficacy of omega-3 PUFAs in depression: A meta-analysis. Translational Psychiatry. 2019/08/05 2019;9(1):190. doi:10.1038/s41398-019-0515-5

- Paddon-Jones D, Westman E, Mattes RD, Wolfe RR, Astrup A, Westerterp-Plantenga M. Protein, weight management, and satiety1. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008/05/01/ 2008;87(5):1558S-1561S. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1558S

- van der Klaauw AA, Keogh JM, Henning E, et al. High protein intake stimulates postprandial GLP1 and PYY release. Obesity (Silver Spring). Aug 2013;21(8):1602-7. doi:10.1002/oby.20154

- Mao T, Huang F, Zhu X, Wei D, Chen L. Effects of dietary fiber on glycemic control and insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Functional Foods. 2021/07/01/ 2021;82:104500. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2021.104500

- Soliman GA. Dietary Fiber, Atherosclerosis, and Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients. May 23 2019;11(5)doi:10.3390/nu11051155

- Delzenne NM, Cani PD, Daubioul C, Neyrinck AM. Impact of inulin and oligofructose on gastrointestinal peptides. British Journal of Nutrition. 2005;93(S1):S157-S161.

- Samuel BS, Shaito A, Motoike T, et al. Effects of the gut microbiota on host adiposity are modulated by the short-chain fatty-acid binding G protein-coupled receptor, Gpr41. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105(43):16767-16772.

- Cani PD, Lecourt E, Dewulf EM, et al. Gut microbiota fermentation of prebiotics increases satietogenic and incretin gut peptide production with consequences for appetite sensation and glucose response after a meal. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2009;90(5):1236-1243.

- Haque A, Khan T, Khan I, Ahmad MF, Ashraf SA. Functional Aspects of Dietary Fibers in Nutraceuticals. In: Amir Ashraf S, Adnan M, eds. Food Bioactives and Nutraceuticals: Dietary Medicine for Human Health and Well-Beings. Springer Nature Singapore; 2025:179-209.