Chlorella Vulgaris: Single-Celled Microalgal Plant Forefathers

Chlorella Vulgaris: Single-Celled Microalgal Plant Forefathers

Chlorella vulgaris is a type of green microalgae with a rich history of nutritional benefit for humans, primarily as a diverse source of macronutrients, micronutrients, and beneficial pigments, such as chlorophyll.

What are Microalgae?

The term “microalgae” refers to a group of singled-celled, microscopic algae capable of photosynthesis and found in both fresh and marine water.1,2 They have been found in all types of environmental conditions all over the world and may have originated as long as 3.4 billion years ago.2 Microalgae have been analyzed as a source of:

- Protein

- Fatty acids

- Carbohydrates

- Pigments

- Vitamins and minerals2,3

The recorded use of microalgae for food dates to the sixteenth century Aztecs.2,4 Microalgae are also common ingredients in products like dyes, pharmaceuticals, animal feed, aquaculture, and cosmetics.2 Though it is likely that more than 20,000 species of microalgae exist, only around fifty have been studied so far.4

Microalgae only need carbon dioxide, water, sunlight, and a handful of minerals for growth. The exact composition of microalgal species can be adjusted and depends on how they were cultivated.5 They are a promising source of sustainable energy because of their ability to collect large quantities of lipids fitting for biodiesel production.6,7

What is Chlorella Vulgaris?

C. vulgaris is a species of microalgae first discovered in 1890, produced in many countries worldwide as one of little microalgae species available as food supplements or additives.2,8 This ancient microalgae is a rich source of nutrition, with many individual nutrient concentrations depending on growth conditions: 3, 9-16

- Protein (42 to 58 percent of biomass dry weight)

- Lipids, including polyunsaturated fatty acids (5 to 40 percent)

- Carbohydrate, primarily starch (12 to 55 percent)

- Potassium

- Magnesium,

- Zinc

- Vitamins A, E, and C

- B vitamins

Potential Health Benefits of Chlorella

Chlorella is believed to offer potential health benefits due to its rich nutrient profile, including vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. Some studies suggest that Chlorella may support immune function and detoxification processes in the body, contributing to overall well-being.

Pigments

C. vulgaris contains a significant amount of chlorophyll, as much as one to two percent of its dry weight.2 Additional pigments found in C. vulgaris include carotenoids like beta-carotene – provitamin A pigments associated with their yellow-orange color. In C. vulgaris, the green-pigmented chlorophyll masks any yellow-orange pigment that might be present. Chlorophyll and carotenoids in C. vulgaris have been studied for their therapeutic properties, including:17-19

- Antioxidant activity

- Retinal health

- Blood cholesterol regulation

- Immune support

Adsorbent activity and detoxification support

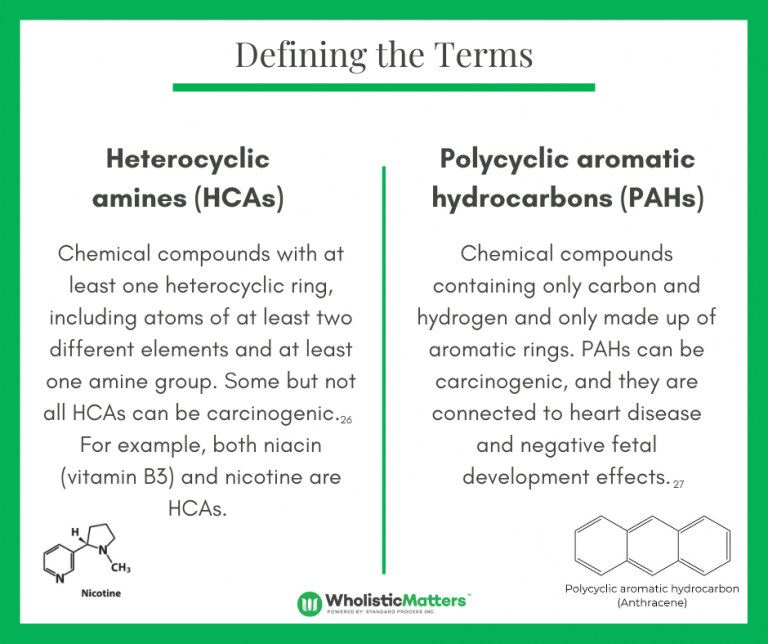

C. vulgaris has been frequently studied for its ability to support detoxification. A 2015 study illustrated the potential of C. vulgaris to detoxify the body of carcinogenic chemicals – heterocyclic amines (HCAs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).20 Another study suggested that C. vulgaris-directed PAH detoxification occurred through epigenetic modulations, such as DNA methylation, that may reduce hypermethylation of genes involved in metabolizing PAHs.21

One of the mechanisms behind the detoxifying potential of C. vulgaris is adsorbent activity. “Adsorbents” bind certain substances to their surface or within their pores, as opposed to “absorbents,” which allow substances to permeate their structure uniformly. C. vulgaris adsorption has shown its ability to help eliminate heavy metal ions from industrial wastewater, synthetic dyes from water, and lead through binding.22-25

C. vulgaris and microalgae in general are tiny but powerful sources of nutrition, including macronutrients, micronutrients, and phytonutrients – a triple threat. They are easy to grow and provide a variety of health benefits for humans, including antioxidant and adsorbent activity.

Support for Glucose and Lipid Metabolism

Supplementation with C. vulgaris in pre-clinical models has demonstrated strong benefits related to glucose and lipid metabolism, pathways that are critical for overall healthy metabolism and function. C. vulgaris supplementation increased glucose uptake in liver and skeletal muscle which contributed to its overall blood glucose-lowering, or hypoglycemic effects. (28)

It was also found to influence the expression of key genes and proteins involved in glucose metabolism, including glucose transporters. (29,30) Similarly, supplementation with Chlorella may help lower serum cholesterol levels by interfering with intestinal absorption of steroids, the precursor of cholesterol, as well as altering gene expression of enzymes involved in cholesterol metabolism. (31-33)

Limited clinical data also supports the ability of Chlorella supplementation to reduce serum lipid markers, including cholesterol and triglycerides in mildly hypercholesterolemic people. (34,35) Together, the ability of C. vulgaris to regulate aspects of lipid and glucose metabolism can benefit human health and overall well-being.

Chlorella Vulgaris in Disease

The ability of C. vulgaris to modulate disease risk has been studied for several conditions, including gastrointestinal conditions as well as cardiovascular disease.

In a mouse model of colitis, supplementation with C. vulgaris positively altered microbial communities in the gut microbiome, resulting in an increase in bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). (36) SCFAs provide many benefits to the gastrointestinal tract, including providing energy for intestinal cells and altering the pH of the gut. C. vulgaris also alleviated symptoms of colitis through modulation of the immune system. (36)

For individuals with heart disease, C. vulgaris may help lessen underlying inflammation and oxidative stress through the presence of vitamins, minerals, and polysaccharides, as well as its healthy lipid content. (37) Other scientific studies have also confirmed the ability of C. vulgaris to positively influence other foundations of health, including liver function, lung health, immune system function, and metabolic markers such as lipids and blood glucose. (38,39)

More on epigenetics:

- Neumann, U., Derwenskus, F., Gille, A., Louis, S., Schmid-Staiger, U., Briviba, K., & Bischoff, S. C. (2018). Bioavailability and Safety of Nutrients from the Microalgae Chlorella vulgaris, Nannochloropsis oceanica and Phaeodactylum tricornutum in C57BL/6 Mice. Nutrients, 10(8), 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10080965

- Safi, C., Zebib, B., Merah, O., Pontalier, P., and Vaca-Garcia, C. (2014). Morphology, composition, production, processing and applications of Chlorella vulgaris: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Elsevier, 35: 265-278. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.04.007

- Becker, W. (2004). Microalgae in Human and Animal Nutrition. Handbook of Microalgal Culture: Biotechnology and Applied Phycology. 312–351.

- Venkataraman, LV., (1997). Spirulina platensis (Arthrospira): physiology, cell Biology and biotechnology. J Appl Phycol, 9: 295-296

- Chia, M.A., Lombardi, A.T., & Melão Mda, G. (2013). Growth and biochemical composition of Chlorella vulgaris in different growth media. An Acad Bras Cienc., 85(4):1427-38.

- Gonzâlez-Fernândez, C., Sialve, B., Bernet, N., Steyer, J-P. (2012). Impact of microalgae characteristics on their conversion to biofuel. Part I: focus on cultivation and biofuel production. Biofuel Bioprod Biorefin, 6:105-13.

- Tran, N.H., Bartlett, J.R., Kannangara, G.S.K., Milev, A.S., Volk, H., Wilson, M.A. (2010). Catalytic upgrading of biorefinery oil from micro-algae. Fuel, 89:265-74.

- Tokuşoglu O., üUnal M.K. Biomass Nutrient Profiles of Three Microalgae: Spirulina platensis, Chlorella vulgaris, and Isochrisis galbana. J. Food Sci. 2003;68:1144–1148. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2003.tb09615.x

- Beijerinck, M. W. (1890). “Culturversuche mit Zoochlorellen, Lichenengonidien und anderen niederen Algen”. Bot. Zeitung, 48: 781–785.

- Becker, E,W. (1994). Microalgae: biotechnology and microbiology. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Morris, H.J., Almarales, A., Carrillo, 0., Bermudez, R.C. (2008). Utilisation of Chlorella vulgaris cell biomass for the production of enzymatic protein hydrolysates. Bioresour Technol, 99:7723-9.

- Safi, C., Charton, M., Pignolet, 0., Silvestre, F., Vaca-Garcia, C., Pontalier, P-Y. (2013). Influence of microalgae cell wall characteristics on protein extractability and determination of nitrogen-to-protein conversion factors. J Appl Phycol. 25:523-9.

- Servaites, J.C., Faeth, J.L., Sidhu, S.S. (2012). A dye binding method for measurement of total protein in microalgae. Anal Biochem, 421:75-80.

- Seyfabadi, J., Ramezanpour, Z., Amini Khoeyi, Z. (2011). Protein, fatty acid, and pigment content of Chlorella vulgaris under different light regimes. J Appl Phycol, 23:721-6.

- Branyikova, I., Marsalkova, B., Doucha, J., Branyik, T., Bisova, K., Zachleder, V., Vitova, M. (2011). Microalgae – novel highly efficient starch producers. Biotechnol Bioeng, 108: 766-76.

- Choix, F.J., de-Bashan, L.E., Bashan, Y. (2012). Enhanced accumulation of starch and total carbohydrates in alginate-immobilized Chlorella spp. induced by Azospirillum brasilense: 1. Autotrophic conditions. Enzyme Microb Technol, 51 :294-9.

- Cha, K.H., Koo, S.Y., Lee, D.U. (2008). Antiproliferative effects of carotenoids extracted from Chlorella ellipsoidea and Chlore/la vulgaris on human colon cancer cells. J Agric Food Chem, 56:10521-6.

- Tanaka, K., Konishi, F., Himeno, K., Taniguchi, K., Nomoto, K. (1984). Augmentation of antitumor resistance by a strain of unicellular green algae, Chlorella vulgaris. Cancer Immunol Immunother, 17:90-4.

- Mishra, V.K., Bacheti, R.K. and Husen, A. (2011). Medicinal Uses of Chlorophyll: a critical overview. In: Chlorophyll: Structure, Function and Medicinal Uses, Hua Le and and Elisa Salcedo, Eds., Nova Science Publishers, Inc., Hauppauge, NY 11788 (ISBN 978-1-62100-015-0), 177-196.

- Lee, I., Tran, M., Evans-Nguyen, T., Stickle, D., Kim, S., Han, J., Park, J. Y., & Yang, M. (2015). Detoxification of chlorella supplement on heterocyclic amines in Korean young adults. Environmental toxicology and pharmacology, 39(1), 441–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2014.11.015

- Yang, M., Youn, J. I., Kim, S. J., & Park, J. Y. (2015). Epigenetic modulation of Chlorella (Chlorella vulgaris) on exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Environmental toxicology and pharmacology, 40(3), 758–763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2015.09.005

- Indhumathi, P., Sathiyaraj, S., Koelmel, J., Shoba, S., Jayabalakrishnan, C. & Saravanabhavan, M. (2018). The Efficient Removal of Heavy Metal Ions from Industry Effluents Using Waste Biomass as Low-Cost Adsorbent: Thermodynamic and Kinetic Models. Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie, 232(4), 527-543. https://doi.org/10.1515/zpch-2016-0900

- Chin, J.Y., Chng, L.M., Leong, S.S. et al. (2020). Removal of Synthetic Dye by Chlorella vulgaris Microalgae as Natural Adsorbent. Arab J Sci Eng, 45, 7385–7395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-020-04557-9

- Sayadi, M.H., Rashki, O., & Shahri, E. (2019). Application of modified Spirulina platensis and Chlorella vulgaris powder on the adsorption of heavy metals from aqueous solutions. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 7(3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2019.103169

- El-Nass, M.H., Al-Rub, F.A., Ashour, I., Al Marzouqi, M. (2007). Effect of competitive interference on the biosorption of lead(II) by Chlorella vulgaris. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification, 46(12), 1391-1399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cep.2006.11.003

- Sugimura, T., Wakabayashi, K., Nakagama, H., & Nagao, M. (2004). Heterocyclic amines: Mutagens/carcinogens produced during cooking of meat and fish. Cancer science, 95(4), 290–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03205.x

- Kim, K. H., Jahan, S. A., Kabir, E., & Brown, R. J. (2013). A review of airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and their human health effects. Environment international, 60, 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2013.07.019

- Cherng, J.Y., Shih, M.F. (2006). Improving glycogenesis in streptozotocin (STZ) diabetic mice after administration of green algae Chlorella. Life Sci, 78:1181.

- Vecina, J.F., Oliveira, A.G., Araujo, T.G., Baggio, S.R., Torello, C.O., Saad, M.J.A., Queiroz, M.L.S. (2014). Chlorella modulates insulin signaling pathway and prevents high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance in mice. Life Sci, 95:45.

- Itakura, H., Kobayashi, M., Nakamura, S. (2015). Chlorella ingestion suppresses resistin gene expression in peripheral blood cells of borderline diabetics. Clin Nutr ESPEN, 10:e95.

- Adnerson, J.W., Deakins, D.A., Bridges, S.R. Soluble fiber: Hypocholesteromic effects and proposed mechanisms. In: Kritchevsky D., Bonfield C., Anderson J.W., editors. Dietary Fiber: Chemistry, Physiology and Health Effects. Plenum Press; New York, NY, USA: 1990. pp. 339–363.

- Cherng, J.Y., Shih, M.F. (2005). Preventing dyslipidemia by Chlorella pyrenoidosa in rats and hamsters after chronic high fat diet treatment. Life Sci, 76:3001.

- Shibata, S., Hayakawa, K., Egashira, Y., Sanada, H. (2007). Hypocholesteromic mechanism of Chlorella: Chlorella and its indigestible fraction enhance hepatic cholesterol catabolism through up-regulation of cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase in rats. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem, 71:916.

- Ryu, N.H., Lim, Y., Park, J.E., Kim, J., Kim, J.Y., Kwon, S.W., Kwon, O. (2014). Impact of daily Chlorella consumption on serum lipid and carotenoid profiles in mild hypercholesterolemic adults: A double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Nutr J, 13:57.

- Kim, S., Kim, J., Lim, Y., Kim, Y.J., Kim, J.Y., Kwon, O. (2016). A dietary cholesterol challenge study to assess Chlorella supplementation in maintaining healthy lipid levels in adults: A double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Nutr J, 15:54.

- Velankanni, P., Go, S.-H., Jin, J.B., et al. (2023). Chlorella vulgaris Modulates Gut Microbiota and Induces Regulatory T Cells to Alleviate Colitis in Mice. Nutrients, 15(15):3293.

- Barghchi, H., Dehnavi, Z., Nattagh-Eshitvani, E., et al. (2023). The effects of Chlorella vulgaris on cardiovascular risk factors: A comprehensive review on putative molecular mechanisms. Biomed Pharmacother, 162:114624.

- Yarmohammadi, S., Hosseini-Ghatar, R., Foshati, S., et al. (2021). Effect of Chlorella vulgaris on Liver Function Biomarkers: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Nutr Res, 10(1):83.

- Panahi, Y., Darvishi, B., Jowzi, N., Beiraghdar, F., Sahebkar, A. (2016). Chlorella vulgaris: A Multifunctional Dietary Supplement with Diverse Medicinal Properties. Curr Pharm Des, 22(2):164.