Accessory Organs of Digestion

Summary

Digestion is an essential process; it allows the body to obtain nutrients from food. It involves the mouth, stomach, and intestines; however, other organs support digestion including the liver, gallbladder, pancreas, and gut microbiome.

What’s the Difference Between Digestion and Absorption?

Digestion and absorption are the processes by which the body receives nutrients from food. Digestion involves the breakdown of food into smaller components, which are then absorbed into the bloodstream and circulated throughout the body.1 The body cannot use food in the form in which it is consumed; it must be broken down via digestion to be utilized. Proteins are broken down into amino acids, carbohydrates are reduced to simple sugars, or monosaccharides, and fat molecules are broken down into free fatty acids and monoglycerides.1 Both processes utilize enzymes and are intricately linked, but they are distinct processes.

Digestion begins in the mouth with the mechanical and chemical breakdown of food. As the teeth work to physically break apart food, enzymes from saliva initiate chemical degradation.1,2 At this point, the chewed food, or bolus, travels down the esophagus. The esophagus utilizes peristalsis, the constriction and relaxation of muscles to produce wave-like movements, to help move the bolus along.1,2 In the stomach, gastric juice, consisting of hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes, further breaks down food into components that can be absorbed and utilized by the body.1,2

| Digestive Enzyme | Digestive Enzyme | Digestive Enzyme |

| Amylase | Mouth and pancreas | Complex carbohydrates |

| Lipase | Pancreas | Fats |

| Protease | Pancreas | Proteins |

| Lactase | Small intestine | Lactose |

| Sucrase | Small intestine | Sucrose |

| Maltase | Saliva | Maltose |

| Trypsin | Small intestine | Proteins |

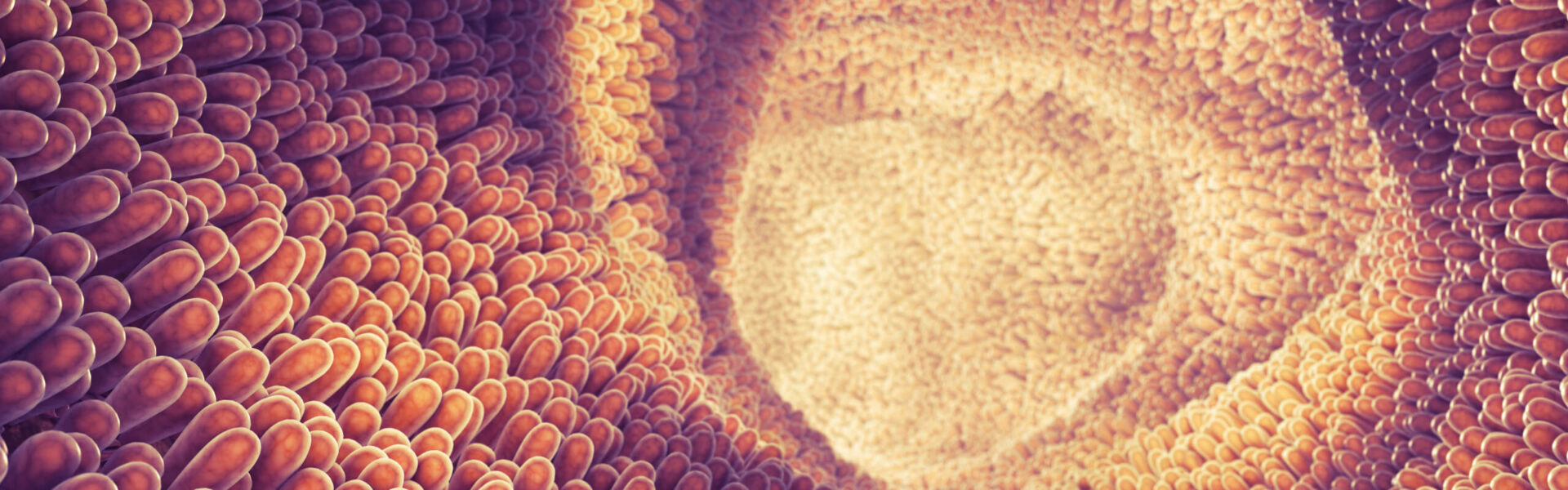

As the digested food, now called chyme, leaves the stomach, it enters the intestinal tract where digestion is completed and absorption begins.1,2 The intestines are uniquely able to maximize absorption through the microvilli of the brush border which significantly increase the surface area of the intestines, allowing for greater contact with food components and consequently enhanced absorption.3 The small intestines are responsible for the absorption of most macronutrients and micronutrients, with different sections specializing in the absorption of certain nutrients.1 Next the large intestines absorb any remaining nutrients or fluids, as well as any water available for reabsorption. After passing through the large intestines, any food particles that were not digested and absorbed are eliminated from the body.

Accessory Organs of Digestion

Digestive processes are not limited to the mouth, stomach, and intestines. Other accessory organs support digestion and absorption including the liver, gallbladder, pancreas, and gut microbiome.

Liver

After nutrients are absorbed in the intestines, they travel to the liver. The liver will process macronutrients and send them back out into circulation to go to the tissues that need them.3 For example, after a meal with high fat content, the liver will direct the proper vehicles to carry the excess fatty acids to adipose tissue for storage. The liver also contributes to digestion through the production of bile.3 Bile aids in the digestion and absorption of lipids via the work of bile salts that help break down dietary fats.3

Gallbladder

Bile produced in the liver is stored and concentrated in the gallbladder. Upon eating, the gallbladder releases bile to help break down fats.4 The gallbladder is able to influence bile flow as well as composition and also secretes bicarbonate and mucins to protect cells from bile-acid induced injury.4 Structural and functional issues can affect gallbladder health including gallstone diseases and cirrhosis.4

Pancreas

The pancreas aids in digestion through the production and secretion of enzymes and hormones. Pancreatic juices contain enzymes that help break down macronutrients into smaller components that can be absorbed.1 It also produces hormones including insulin and glucagon, which are important messengers in the body that can direct other organs in the digestive system and support metabolism.5,6 The physiology of pancreatic hormones and secretions is complex, integrating various levels of control and regulation to ensure digestion, absorption, and metabolism run efficiently.5,6

Insulin and glucagon are also the primary controllers of blood glucose metabolism, which includes the digestion and absorption of carbohydrates. When the body encounters a large influx of glucose from food, the pancreas will increase its secretion of insulin to direct cells to transport glucose out of the bloodstream and into tissues. Conversely, when blood glucose levels drop too low, the pancreas releases glucagon to signal to the liver to break down glucose reservoirs to raise blood sugar levels. Insulin and glucagon regulate digestion via suppressing or stimulating hunger, respectively.5,6 Dysregulated glucose metabolism, including aberrant insulin and glucagon secretions, is a hallmark of type 2 diabetes.

Gut microbiome

There is debate about whether the gut microbiome is an official “organ” of the body. Functionally, it interacts with the body like other organs do, and it supports healthy digestion and absorption. Some bacterial residents of the gut microbiome are able to digest food components, mainly dietary fibers, that the body cannot break down.7 They utilize these undigestible compounds and produce beneficial metabolites including short-chain fatty acids which then increase the health of intestinal cells.7 Short-chain fatty acids have multiple beneficial effects including anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, and antimicrobial effects in addition to their ability to enhance gut integrity and support cellular processes.7,8 Some bacteria can also modulate gut barrier integrity and overall GI health, which supports digestion and absorption abilities.7

Digestion and absorption can be overlooked processes until an issue arises. Optimizing the health of the GI system and its processes should target the obvious digestion organs including the stomach and intestines, as well as accessory organs. Consuming a whole food-based diet, rich in dietary fibers and bioactive phytochemicals can help support the health of accessory organs and the gut microbiome. Additionally, probiotics support GI health and digestion via the gut microbiome, and engaging in regular physical activity helps with intestinal motility to keep digestion running smoothly.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease. (2017). Your Digestive System & How it Works. Available at: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/digestive-system-how-it-works.

- Ogobuiro, I., Gonzales, J., Tuma, F. Physiology, Gastrointestinal. [Updated 2022 Apr 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537103/.

- Kalra, A., Yetiskul, E., Wehrle, C.J., Tuma, F. Physiology, Liver. [Updated 2022 May 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535438/.

- Housset, C., Chretien, Y., Debray, D., Chignard, N. (2016). Functions of the Gallbladder. Compr Physiol, 6:1549.

- Al-Massadi, O., Fernø, J., Diéguez, C., Nogueiras, R., and Quiñones, M. (2019). Glucagon Control on Food Intake and Energy Balance. Int J Mol Sci, 20(16):3905.

- Woods, S.C., Lutz, T.A., Geary, N., Langhans, W. (2006). Pancreatic signals controlling food intake; insulin, glucagon, and amylin. Phils Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 361:1219.

- Valdes, A.M., Walter, J., Segal, E., Spector, T.D. (2018). Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. Brit Med J, 361:k2179.

- Tan, J., McKenzie, C., Potamitis, M., Thorburn, A.N., Mackay, C.R., Macia, L. (2014). The role of short-chain fatty acids in health and disease. Adv Immunol, 121:91.