Health Effects of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Gut and Beyond

Health Effects of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Gut and Beyond

Food fuels the body, for better or worse. Some dietary choices are healthier, providing phytonutrients, lean protein, and fiber, while others offer very little nutritional value, such as highly processed, refined foods. When food is broken down during digestion and absorption, the smaller nutrient components are absorbed and utilized throughout the body, or excreted. Proteins are broken down into amino acids, fats are degraded to free fatty acids and monoglycerides while carbohydrates are reduced to simple sugars. Dietary fiber from carbohydrates, on the other hand, cannot be broken down. Instead, fiber is fermented by bacteria found in the gut microbiome, which produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in the

process.1-4

What are Short-Chain Fatty Acids?

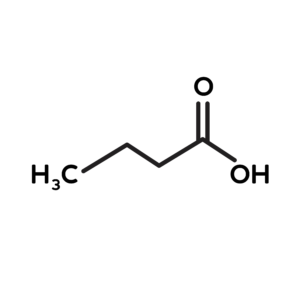

SCFAs are a group of saturated fatty acids that are made up of six or fewer carbon (C) atoms. Acetate (C2), propionate (C3), and butyrate (C4) comprise the majority of SCFAs produced by bacteria in the colon.1-5 SCFAs work through two pathways:6

- Activate G protein-coupled receptors and their downstream pathways, acting as cellular signaling messengers

- Inhibit histone deacetylases, enzymes involved in regulating gene expression

Control of gene expression via SCFAs results in two major changes: decreased production of inflammatory cytokines and immune system modulation.1

Figure 1: Butyric acid (Butyrate)

Butyrate is the most studied SCFA and shows promise as a therapeutic option for several diseases including diabetes, obesity, and cancer.1,4 It plays a key role in cellular energetic pathways as well as whole-body energy metabolism.3,4 It is also the primary source of energy for colonocytes, the epithelial cells of the colon.1-5 As much as 95 percent of the butyrate produced by the gut microbiome is utilized by intestinal cells for energy while the remaining five percent travels to the liver after absorption where it is processed and directed to other organs.4

Short-Chain Fatty Acid Foods

SCFAs are generated primarily in response to the presence of undigested dietary fibers in the colon. Insoluble dietary fibers are resistant to the fermentation that would yield SCFAs, but soluble dietary fibers can be fermented. Soluble dietary fibers include pectin, beta-glucans, fructo-oligosaccharides, and inulin.4 Additionally, butyrate is found in dairy products including milk, butter, and cheese as well as human breast milk; it can also be produced via amino acid-fermenting bacteria, but this accounts for a very small portion of total butyrate levels.4,7 SCFA supplements have been developed with positive results; however, taste is not well-tolerated.6

There are a handful of other dietary compounds that can prompt SCFA production by increasing the growth of Bifidobacteria, which produce SCFAs.1 The extracts of culinary spices like oregano, ginger, rosemary, cinnamon, black pepper, and cayenne pepper, and turmeric increased SCFA levels, as did the B vitamin riboflavin.8-10 Several herbs can also increase SCFA levels or the bacteria that produce them, including Plantago asiatica and Cyclocarya paliurus.11 Additionally, prebiotics and probiotics can help enhance SCFA production by providing soluble fiber for digestion (prebiotics) and increasing levels of bacteria that are capable of fermenting dietary fiber (probiotics).5

Why We Need Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Diet

SCFAs exhibit many health-promoting properties. In general, they are anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and anti-cancer.1,2,5,12 Specifically, they promote differentiation of immune cells while downregulating pro-inflammatory mediators.5 They are also involved in regulating lipid metabolism, modulating mitochondrial function, and suppressing food intake.2,4 SCFAs are also able to promote healthy blood glucose metabolism in several organs:1-4

| Organ | Beneficial Effect |

| Liver | Decrease lipid accumulation, glucose production, and lipogenesis |

| Skeletal Muscle | Improve insulin sensitivity and mitochondrial function |

| GI tract | Increase intestinal production of glucose and release of appetite hormones |

| Adipose tissue | Stimulate leptin release, increase energy expenditure, decrease lipid accumulation, and modulate inflammation |

When there is not enough fiber present in the diet, the gut microbiota are unable to produce SCFAs at levels sufficient to exert beneficial effects.6 This can lead to inflammatory conditions in the gut and throughout the body.5,6

How Do Short-Chain Fatty Acids Support Gut Health Specifically?

Butyrate is primarily responsible for feeding the cells that make up the gut lining, but SCFAs also support gut health through other mechanisms. They strengthen gut barrier function and maintain permeability, modulate gut microbiome composition, enhance bowel function, protect against potential infections, and reduce gut inflammation.1,6,7,13 They also decrease intestinal pH, which creates an unfavorable environment for pathogens while promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria.7 In a pre-clinical study, a diet lacking soluble fiber led to gut inflammation and poor intestinal health leading to weight gain; however, when fiber was re-introduced, intestinal health quickly improved.14

How Are Short-Chain Fatty Acids Absorbed?

SCFAs produced in the gut can be absorbed via proteins in the intestinal epithelial cells.5 SCFAs are absorbed via diffusion, ion exchange, and active transport.3 They can enter portal circulation and travel to organs that can utilize them including brain, skeletal muscle, and immune cells.3,5 This allows these gut-specific metabolites to benefit many other areas of the body. Acetate, for example, is able to cross the blood-brain barrier where it regulates appetite.3 SCFAs have been implicated in protection from or therapeutic options for several diseases including obesity, type 2 diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, and certain cancers.1-5,12

Learn more about the gut microbiome from Standard Process. WholisticMatters is powered by Standard Process, a nutritional supplement company family-owned and operated for over 90 years. Standard Process offers many nutritional solutions.

- Tan, J., McKenzie, C., Potamitis, M., Thorburn, A.N., Mackay, C.R., Macia, L. (2014). The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Health and Disease. Adv Immunol, 121:91.

- Mazhar, M., Zhu, Y., Qin, L. (2023). The Interplay of Dietary Fibers and Intestinal Microbiota Affects Type 2 Diabetes by Generating Short-Chain Fatty Acids. Foods, 12:1023.

- Anachad, O., Taouil, A., Taha, W., Bennis, F., Chegdani, F. (2023). The Implication of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Obesity and Diabetes. Microbiol Insights, 16:11786361231162720.

- Peng, K., Dong, W., Luo, T., Tang, H., Zhu, W., Huang, Y., Yang, X. (2023). Butyrate and obesity: Current research status and future prospect. Front Endocrinol, 14:1098881.

- Gomes, S., Rodrigues, A.C., Pazienza, V., Preto, A. (2023). Modulation of the Tumor Microenvironment by Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids: Impact in Colorectal Cancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci, 24:5069.

- Kirundi, J., Moghadamrad, S., Urbaniak, C. (2023). Microbiome-liver crosstalk: A multihit therapeutic target for liver disease. World J Gastroenterol, 29(11):1651.

- Dahl, S.M., Rolfe, V., Walton, G.E., Gibson, G.R. (2023). Gut microbial modulation by culinary herbs and spices. Food Chem, 409:135286.

- Lu, Q.-Y., Rasmussen, A.M., Yang, J., Lee, R.-P., Huang, J., Shao, P., Carpenter, C.L., Gilbuena, I., Thames, G., Henning, S.M., Heber, D., Li, Z. (2019). Mixed Spices at Culinary Doses Have Prebiotic Effects in Healthy Adults: A Pilot Study. Nutrients, 11(6):1425.

- Peterson, C.T., Rodionov, D.A., Iablokov, S.N. Pung, M.A., Chopra, D., Mills, P.J., Peterson, S.N. (2019). Prebiotic Potential of Culinary Spices Used to Support Digestion and Bioabsorption. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med, 2019:8973704.

- Liu, L., Sadabad, M.S., Gabarrini, G., Lisotto, P., von Martels, J.Z.H., Wardill, H.R., Dijkstra, G., Steinert, R.E., Harmsen, H.J.M. (2023). Riboflavin Supplementation Promotes Butyrate Production in the Absence of Gross Compositional Changes in the Gut Microbiota. Antioxid Redox Signal, 38:282.

- Wang, L., Gou, X., Ding, Y., Liu, J., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, J., Du, L., Peng, W., Fan, G. (2023). The interplay between herbal medicines and gut microbiota in metabolic diseases. Front Pharmacol, 14:1105405.

- Rasouli-Saravani, A., Jahankhani, K., Moradi, S., Gorgani, M., Shafaghat, Z., Mirsanei, Z., Mehmandar, A., Mirazei, R. (2023). Role of microbiota short-chain fatty acids in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. Biomed Pharmacother, 162:114620.

- Birkeland, E., Gharagozlian, S., Valeur, J., Aas, A.-M. (2023). Short-chain fatty acids as a link between diet and cardiometabolic risk: a narrative review. Lipids Health Dis, 22(1):40.

- Chassaing, B., Miles-Brown, J., Pellizzon, M., Ulman, E., Ricci, M., Zhang, L., Patterson, A.D., Vijay-Kumar, M., Gewirtz, A.T. (2015). Lack of soluble fiber drives diet-induced adiposity in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 309(7):G528.